How can we kill the ghosts of the 20th century?

Or less poetically: how, in the 2020s and beyond, can we render Hitler, Stalin, Mao, and friends irrelevant?

This seems like a long, slow process. But it’s actually an action item—one reader is requesting a subscription refund, because Stalin (“and maybe even Hitler”) are being rehabilitated in the comments. As a Soviet Jew (hardly an unusual reader profile), he finds this problematic. Not surprisingly!

Marc Antony figured out the right line on this. We do not need to praise Hitler, Stalin or Mao. We need to bury them: to make them part of history.

Panta rhei: the present keeps on flowing into the past. As it flows it passes through a filter, which turns news into history. News is for children; a child’s mind is a jungle of myths, in which saints battle demons; news never was anything but a tool of power.

The process of refining news into history is a process of exorcism, in which all magic legends are dispelled and put to rest; and all the characters are mere humans after all. The purpose of news is to be useful. The purpose of history is to be beautiful.

Being beautiful of course requires being true. But it turns out that being useful usually also requires being true—though for different reasons. So refining history is mostly not about correcting actual lies, though sometimes it is. Truth goes way beyond facts.

If your goal in doing history is to forge a tool, or still worse a weapon, you are doing it wrong. You will get a shitty tool and a shittier weapon. The real thing is the best tool, and the best weapon, that it can possibly be.

History is for adults. So it can’t have any ghosts, legends, saints or demons in it. Right?

Hitler, Stalin, Mao and now

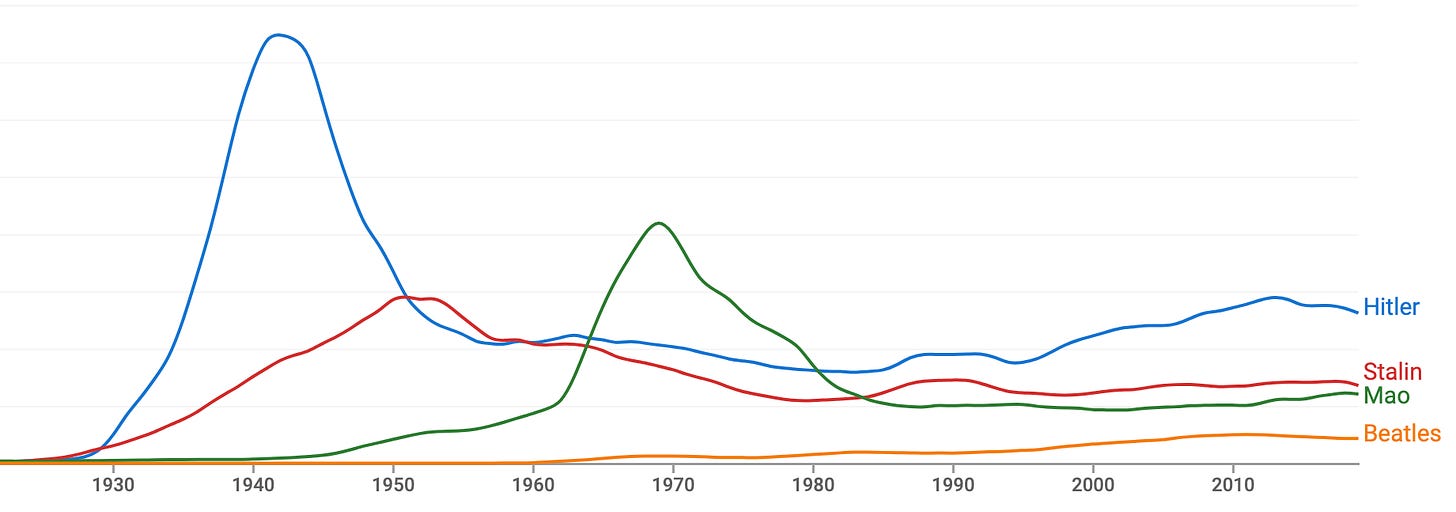

When we look at this lineup, the first anomaly that jumps out at us is the obvious one. Today, Hitler is much more relevant than Stalin—who is still more relevant than Mao:

This is a little odd from a historiographic perspective, because the most salient reason for the continued relevance of these political leaders, who are of course dead, would be the continuing existence of their political movements and/or organizations. Yet Hitler, by far the most extinct of the three, is also by far the most relevant of the three.

Whereas Mao is on the Chinese one-dollar bill. And hardly anyone in China wants to cancel Mao, or has an emotional reaction to handling Chinese money (though I guess they all pay with their phones now—those clever Celestials!), or even really bothers to deny his crimes. Is this weird? Or is it grownup? Or is it just Chinese?

From the standpoint of the mental health of the public, it would be a great victory to reach the point where Hitler is as irrelevant (in the public mind) as Stalin and Mao. It would be such a great victory that, like most victories, it is probably regime-complete. But if a Nazi is anyone who thinks Hitler doesn’t matter, I am definitely a Nazi—and Nazism is definitely the wave of the future—so I recommend against this definition.

Of course, Hitler is a real historical figure; so far as I can determine, our professional historians’ picture of him and his regime is if anything unusually accurate; we also have reasonably sound pictures of Stalin and Mao; and these people do matter in a historical sense, just as Nero, Tamerlane and Robespierre matter; they were human, their sagas are true and illustrate the human condition; but no one at all is worried that Tamerlane will come back and sack Brooklyn—he does not matter in any concrete sense.

Even once we correct the Hitler anomaly, though, we still have to admit that Stalin and Mao matter more than Tamerlane. Partly this is because organizations they led have continued into the present (more so for Mao). Partly, though, this is because we have not yet drawn a clear line between the centuries; we do not understand why the things that happened in the 20th century could not happen today. The feeling of safety is always a matter of such understanding.

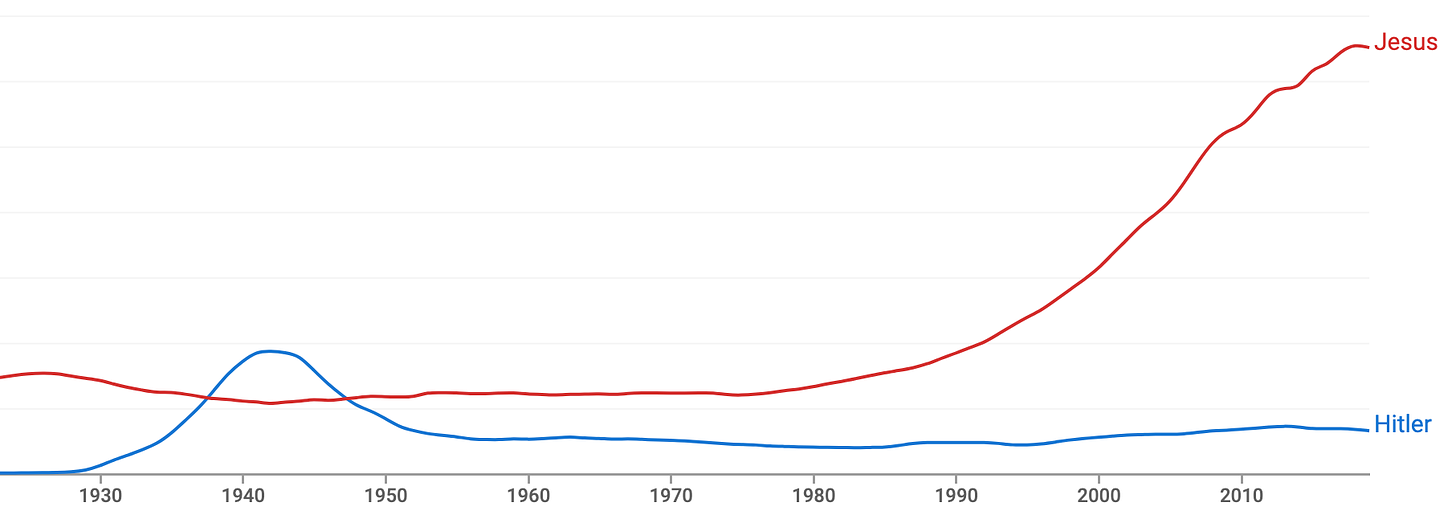

And while Peak Hitler may have come and gone, let’s not forget who still the king:

I am honestly at a loss to explain the red line. But maybe it’s just above me.

The fires of a dead century

In some ways, I think of the war, destruction and massacres of the 20th century as a kind of forest fire. These fires have many tragic consequences. Yet war is a natural part of history, as fire is a natural part of the forest.

In many Western forests we see two types of fire: the surface fire and the crown fire. The surface fire burns off undergrowth and keeps the ecosystem healthy; the crown fire goes to the tops of trees and destroys everything. The 20th century was a kind of crown fire of history, destroying all old-growth regimes, leaving a global monoculture of saplings and weeds.

In this metaphor, these great crown fires cannot happen again because they depend on an accumulated fuel load—a potential energy of violence—which has been burned off. Smoking in an old-growth forest is one thing. Smoking on a rainy day in a burn zone full of weeds and charred timbers is another. That’s why it’s safe to joke about Hitler—or why it should be safe. If Hitler still existed, how would these jokes even be funny?

In a sense, the intellectual freedom we should enjoy today is the real patrimony of our ancestors, who survived these terrible fires. If you’re a real historical romantic, my right to joke about Hitler, to treat him and his regime as part of the past rather than part of the present, was earned by my grandfather, a Stalinist Jew who fought in the Battle of the Bulge—helping make the Third Reich part of the past, not part of the present—helping the Red Tsar hang an iron curtain (in Goebbels’ words) over Europe…

That we should still, in 2021, be ruled by Hitler? Or Stalin? And if you fear Stalin, you are still in a sense ruled by Stalin. The present belongs to the living, and none of these people deserve to be part of it.

Once we cease to fear these people, we can even recognize them as the flawed geniuses they were. No historian doubts the genius of Hitler, Stalin, FDR, Churchill or Mao. Once we recognize the 20th century as part of then, not part of now, we can even recognize the usual brutal historical ironies—so typical of the ultimate storyteller.

If in 1943 you want a clear picture of Moscow, you will not find it in Washington or London. You have to go to Berlin—then subtract the international Jewish conspiracy. Which Hitler keeps expecting to actually care about his murder of the Jews. If in 1941 the international fascist conspiracy is real, Japan attacks Russia instead of Hawaii, Italy attacks Russia instead of Greece, Spain takes Gibraltar and Hitler wins the war—or at least, the Old World. And in 1945 the Anglo-Americans are truly shocked to learn that the false atrocity propaganda of the last war, from which they had refrained in this war—in favor of ranting about the international fascist conspiracy, and its plot for world domination—had, in the hands of this generation of Hun, become entirely true. Which was slightly inconvenient, because they had actively debunked the reports they heard! Meanwhile they themselves had adopted, perfected and industrialized the doctrine of massive air attacks on “civilian housing” to destroy morale—a strategy made in Fascist Italy by General Douhet, which was deployed by all sides except the Soviets, who must have been geniuses or something—because Douhetism did not work at all. It did kill a lot of little girls, though—if not so many as the Aktion Reinhard. The Red Army had a different use for girls—one America’s anti-fascist paladins never even winked at, even whilst stuffing the bear with Midwestern trucks, airplanes, dollars and corn… one can, as always, explain why this (any of this!) was necessary. But try saying it out loud…

Can you blame anyone for not finding the saintly path through this ironic nightmare? I can blame anyone for killing little girls. I certainly cannot blame anyone for being on any side—which is exactly how I feel about the Wars of the Roses, the Peloponnesian War, etc, etc.

This is the historical narrative of the 20th century—a Shakespearean tragedy, as bitter as it is funny—if anything colder than hell can be funny—which, to the living, it must. It shares nothing except for (mostly) the facts with the official narrative, which is an almost pagan myth of good and evil. But it shares little more, and often less, with most attempts to revise that narrative—which tend to simply invert the official myth.

But the leaders, though—the great dictators, including ours—who were they, really? What were they all but flawed and reckless geniuses? Each had their own particular faults, and their own particular talents; they all played as different countries; they all played in a forest ready to be set alight. And they all threw off showers of sparks. And sure: they were all narcissistic, Machiavellian sociopaths. All in such different ways!

They were all smokers in a tinderbox world, a world full of men ready, willing and able to do enormous violence to other men. Their minds fell into the hands of theories that told them they had to do this violence to save their country or the world; so the fires burned, sending up Nicholson Baker’s “human smoke” (a fabulous book, by the way). I am sure they all lived and died in the conviction that they were doing the right thing—as almost all humans do.

Smoking is hazardous to your health—whether in an old-growth forest, or a burned-out field of weeds. I do not advocate smoking. I do not advocate anything. However, our present situation of “low fuel load” is a genuine opportunity for humanity.

It means that enormous changes in political structure are possible, without the risk that the small but inevitable sparks will land on some pile of leaves and burn down the planet again. If this is because the last century already torched it all, we deserve that silver lining. There will never again be a century even remotely like the 20th.

Park regulations in the rainy season

In 2021 there are no ideas that can burn down the world. In 1921 almost any idea could burn down the world—since almost any idea, if it could get enough time on the radio, could recruit an army of serious, determined and capable followers. And indeed the weird and crazy things whole populations believed, even on our side, are indescribably weird by 2021 standards; and they would act on these beliefs, too—even act violently.

We can pseudo-quantify this by defining the concept of political potential: the potential of a population to act collectively outside sovereign control—to align en masse against, or independent of, power. (Enthusiasm in support of power does not count.)

The citizens of Rome in 200BC have high political potential; the citizens of Rome in 200AD have low political potential. The citizens of Rome in 200BC have functioning republican institutions; in 200AD, they do not. It is easy to assume that the drop in political potential is the result of the decline of the institutions; it seems more likely to be the other way around.

Voting is the weakest and most symbolic way to measure collective energy, because voting is a purely symbolic act. Collective violence or threatened collective violence—meaning mob violence or paramilitary organization—measures a much higher level of political engagement.

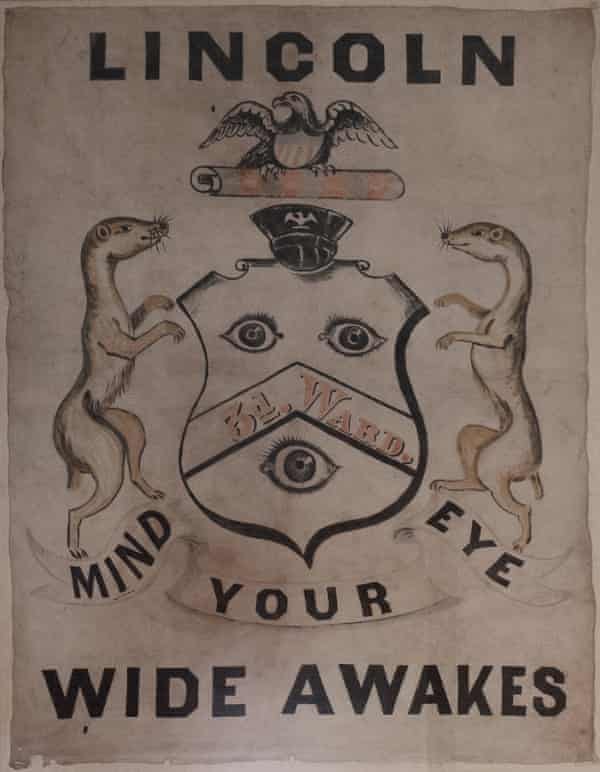

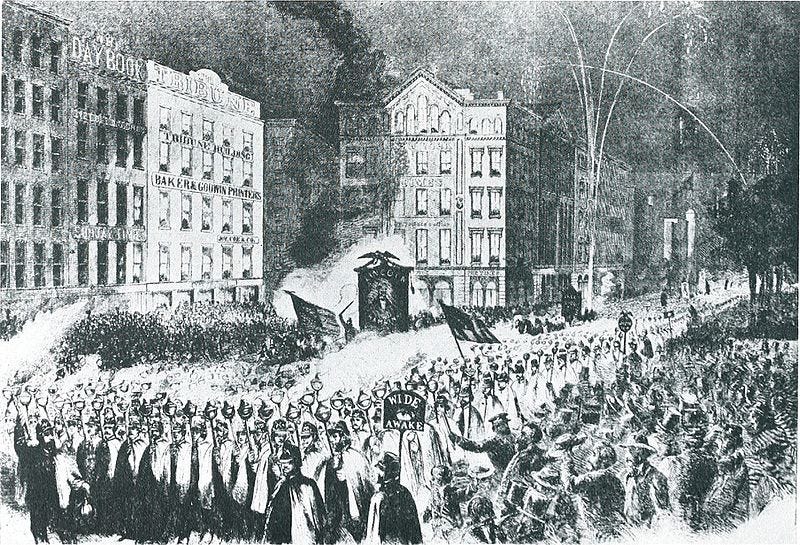

Since there are paramilitary right-wing and left-wing organizations today in America (antifa, “Proud Boys”), we can compare them to history on an apples-to-apples basis. Not only can we compare them to a 20th-century classic like Hitler’s SA, we can compare them to old American classics like the Sons of Liberty, or the Wide Awakes:

The logo of the Wide Awakes was the all-seeing eyeball. A nod to Emerson? Apparently their totem animal was—the weasel? No, the ferret. And they certainly had the eyeballs to ferret out a lot! Because there were 500,000 Wide Awake members—per capita, the equivalent of 10 million in America today.

Mind your eye! Have you ever been to Hartford, Connecticut? Here is Hartford, once upon a time. There were thousands of these proto-Nazi torch-and-eyeball marches.

Bet no one ever told you about this lol. The true history of America is that America, D.H. Lawrence’s “great death-continent,” has never stopped being lit. And maybe the real Lincoln Project is bringing back the Wide Awakes? Professor Jaffa, who sees in Honest Abe a fellow philosopher, could not be reached for comment. Mind your eye!

It seems like a reasonable assessment that, by any metric, the Wide Awakes or the SA exceed the “Proud Boys” by quite a few orders of magnitude in political potential. Of course, the SA were war veterans and the WA… future war veterans. We can even look at the Indiana Klan of a hundred years ago, which had 250,000 members in one state. Now all they have is Snapple! Now, imagine Rose City Antifa going up against the Hartford Wide Awakes. That’d be a strictly pay per view event…

Past or present, at home or abroad, our violent mobs and paramilitary militias look like a joke compared to the parties in any serious domestic conflict—and we sense that if they were not trying to reenact the myths of the past, modern Americans would never try to engage in these behaviors.

In fact, if we didn’t have elections, would we invent them? Why? Do we have a positive national opinion of politics and politicians? This is just how subjects of monarchies in all periods have thought about the idea of elections, if they thought about it at all: a recipe for incompetence and corruption at best, and civil war at worst. Certainly that’s what it was for the last century before the Caesars. The only difference in our mindset is that we prefer oligarchy, not monarchy, to democracy. We call oligarchy a republic; Augustus called monarchy a republic. Democracy has always had the best optics.

It may seem strange to talk of the despots of the 20th century as democratic—but this is exactly what they were. They were able to do enormous violence because their base of support was both enormous and violent. By the start of the war, though there were certainly moderate and radical approaches, and though not even the radicals dared to talk literally and in public about mass extermination, the German consensus that Jews were a problem was as democratic as our consensus that climate change is a problem. Which does not tell us anything about Jews or climate change—just democracy.

Hitler was a democrat because Hitler had a mandate; so did Stalin; they engineered these mandates themselves; so did most everyone else who ever had a mandate. The German masses did not want to murder the Jews; they did want to eliminate the Jews. And if state murder came easily to the nation of Bach and Goethe, how much more easily would it come to the nation of Ivan the Terrible? No offense, Russian friends!

We still do see these 20th-century phenomena in the 21st century—in the world’s most backward backwaters, places like Burma (“Myanmar”). And even a Burmese ethnic cleansing, or a 21st-century Uyghur camp, is a garden-party next to Stalin or Hitler. (PS: can you get banned from Substack for deadnaming a country?)

Furthermore, the early 20th century was a very unusual blend of insanity and capacity. Everywhere in the industrial world, things got done in a fraction of the time they take today, with a fraction of the technology. There can never be a California Holocaust: they’d have to build the railroad first.

The tectonic cause

All these, though, are symptoms. We could imagine the symptoms curing themselves. We could even imagine a California that could build the infrastructure of genocide! We cannot imagine a California that would.

The energy of the century’s crown fires came from one tectonic cause: the conflict of a parochial, premodern mindset with a cosmopolitan, modern mindset. In a sense, these wars were created by a sort of social voltage differential—a world in which premodern, modern, and postmodern worldviews all exchanged electrons. They can never happen again because the premodern world has been destroyed—for better and for worse.

Look at Germany in the 1920s, for instance. The chic people in Berlin cabarets could walk into a time machine and walk straight into Berlin in 2021; they would barely have to update their clothes and accents, which would be quaint and charming; their ideas would be fine. Berlin today would feel like total satanic madness to the average Hitler voter; the same for Indianapolis today, to the average Indiana Klansman. Today such cavemen, placed anywhere in the world, would stick out like Homo erectus at an orgy.

There are individuals who have antiquated views today. There is no society. And even these individuals acquired their views in the postmodern way, individually, not the premodern way, from their parents. In fact, even the Indiana Klansman probably first heard about the Indiana Klan on the radio. (There is no real connection between the 19th-century and 20th-century Klan—the latter was born as a media phenomenon.)

The premodern world and the premodern mindset have been burned to the ground. The social opinions of the average Fox News watcher are well left of President Carter. Modernity has won—and the last thing modernity is prepared to do is to have a civil war with itself. Even if it needs one.

While history’s plates will hopefully never fuse, the next tectonic crash is not between modernity and premodernity, but modernity and postmodernity. That said, there are huge numbers of people in the world who have not fully passed through modernity—but few indeed who have been untouched by it, and those few live in cultures which have rigorously isolated themselves from it.

When we look at the crown fires of the 20th century, we see that the fuel that stokes them is a very particular mindset—a mind with the sincerity, energy and faith of the premodern era, that gets one or two big modern ideas into it.

This submodern mind, not yet jaded by the psychedelic bazaar of ideas, but escaped from the old shackles of old-growth tradition, discovers an easy new path to certainty: fighting for the nation, the race, the class, the leader, or some other big idea. The mind is a completely unironic mind; it swallows this pill completely, and makes it a religion. The submodern mind is open in exactly the wrong way.

One of the ironies of the Third Reich is that while most Nazis were quite submodern, Hitler himself was remarkably postmodern. Anyone reading the Table Talk, really the pons asinorum of Hitler Studies, will be struck by the echo of the 4chan nerd—who in real life is typically an underachieving, overbright, undereducated, maladjusted misfit. Like Hitler. But the thing is: there are no panzer divisions of 4chan nerds.

The fuel of the 20th century’s fires was this vast population of submodern minds—the most fertile ground imaginable for dangerous ideas—a world almost inherently at war with itself. The submodern stage—the stage in which a society can latch on to its first simple modern idea with the absolute conviction of a duck imprinting on its mother—lasts at most one generation. Even if the submodern world had somehow managed to avoid setting itself on fire, this flammable world would still be a memory.

The postmodern condition

It is not that it is hard to convince vast numbers of 21st-century Americans of strange ideas which are totally contrary to the official narrative. It is easy—too easy. All kinds of people can attach to all kinds of ideas. But they are postmodern people and attach in a postmodern way—their engagement is extremely shallow and ineffective.

For example, if the 75 million Trump voters organized like the Wide Awakes—possibly even reusing the paraphernalia, or at least the eyeball—no power could resist them. They would not even have to wait for an election. They could take over the government whenever they wanted, and just start governing. But how would they know what to do?

The Wide Awakes, though invigorated by the startling energy of Lincoln’s American nationalist ideology, were working within premodern patterns of social organization: paramilitary, para-religious, and para-governmental. The Trump voters who are their descendants have lost all of this premodern social capital. They do not even know what it would even mean to exercise collective power in a non-symbolic sense. Little wonder that when they try to play the game, they are easily trapped into cargo-cult democracy.

In most periods, most peoples are in this condition. Like the Romans of the Empire, they are depoliticized. Their political behavior has degenerated into ritual, inevitably-emotionless obeisance to the status quo, plus various symbolic surrogate activities which are transparently without any significant effect.

Most of these symbolic activities are symbolic precisely because of their refusal to acknowledge the difference between high and low political energy. In a world with a heavy fuel burden, these fireworks would be serious indeed. In our burned-over world, they are futile and sterile. But since everyone involved in these surrogate activities mistakes them for real efforts directed at a real result, and since this misperception is no less useful to their enemy, the delusion becomes universal.

A political ideology or organization which was substantive rather than symbolic would have to be engineered to work with the low political potential available. Indeed today’s political consultant class asks almost nothing from the citizen—not blood, sweat or tears; just votes, donations and merch. The rhetoric on the politician’s teleprompter, though, remains that of Dunkirk. At least wild gesticulation went out with Hitler.

The persistent pattern of the modern political discourse, on both sides, is to talk about tiny things in big language. This provides the discourse with a remarkable immunity to big ideas: unless similarly inflated, which makes them sound grandiose, they sound similarly tiny. Because we keep having these big-sounding conversations, we have no idea how thoroughly depoliticized we are.

In this environment, the only ideas that stand out without puffery and exaggeration are not just big ideas, but existential ideas. The older any system is, the more likely that any realistic change is existential; but it is human nature, or at least one kind of human nature, to prefer unrealistic incremental strategies to existential strategies—which are always realistic, unless all the people who could support them are chasing unrealistic incremental strategies. If everyone is working hard to untie the Gordian knot, no one is available for the project of cutting it—which is always possible, and never trivial.

An efficient revolution is a safe revolution

We conclude that any return of existential politics to the modern democracies will have one critical difference from the existential politics of the early 20th century: it will have to operate at much lower energy levels. It will not be a violent politics, but an efficient politics—turning low energy into high impact.

This energy deficit is the reason why there is no such thing as a dangerous idea—not in the early 20th-century sense. Furthermore, support for the hypothesis that there is a low-energy existential politics comes from the Soviet bloc in the late 20th century—which experienced full regime change with little or no violence, except in Romania.

Randos, of course, will always run amuck—for all sorts of reasons. If we had a Music Police which could have prevented the Beatles from recording the White Album, the Manson Family would never have heard “Helter Skelter.” But unstable teenagers are hardly the Holocaust, and hardly a reason to discard even one toenail clipping of the Areopagitica—they are a reason to keep a better eye on unstable teenagers.

But an efficient revolution is a velvet revolution—about as violent as a company going bankrupt. About as violent as the dissolution of East Germany. Without the political fuel load of the early 20th century, the revolution just can’t waste energy on violence. An efficient revolution has to be a safe revolution. It has to make everyone’s life better; its budget for collateral damage is, if not zero, almost zero.

A low-energy revolution is possible because, as the utopian faith of modernity ages, it ripens into a nihilistic and faithless postmodernity. The modern faith in government—which, had the Nazis or Soviets come out on top, would be a faith in a Nazi or Soviet modernity—is like an old piece of tape that has lost its “stick.”

The consequence is a postmodern audience that believes in nothing, that processes everything through irony, and that is completely devoid of any real faith or loyalty. While there are many challenges in inculcating a revolutionary consciousness in such a population, its extremely weak attachment to the regime is an enormous advantage. Tons of people mourned Stalin sincerely. How many mourned Ceausescu sincerely?

While these regimes are heavy, they are not bolted to their foundations. Only gravity holds them upright. Once they start falling, they won’t stop. Once they hit the ground, they won’t come back together. This is exactly how it was with the USSR.

The next regime

But even if we show that the transition to the next regime can be accomplished safely—an American velvet revolution—what about that next regime itself?

Both our desire to exorcise the ghosts, and power’s desire to keep them around, stem from the same cause: the ghosts are power’s best insurance.

There are three political forces: monarchy, oligarchy and democracy. Every regime is based on one and suppresses the other two.

Democracy is the strongest but least stable force; truly democratic regimes are rare. Oligarchy is the most stable force; it is especially good at suppressing democracy, because it is especially good at pretending to be democracy. The only threats to an oligarchy are either a foreign oligarchy, or a union of democracy and monarchy—in which democratic energy installs a monarch.

It is very easy to show that, when democratic energy is weak, monarchy is the only possible successor of oligarchy. In general and with only clearly limited exceptions, the first job of any new regime is to dismantle and replace the institutions of the old. Like any other serious task, only unity of command can solve this problem.

In a true, high-energy democratic revolution, there is another way. The revolution’s leaders can destroy anything by lifting a finger: just stop protecting it from the mob. So it was in 1775, 1789 and 1917. As for replacing the institutions, there is never a shortage of mob leaders who want fancy titles and the power that goes with them.

The “mob” that pushed its way into the Capitol building in 2021 had been stewed since birth in the language of 1775, 1789 and even 1917. But they were nothing at all like the submodern people who made those revolutions. So they got a little rowdy in a couple of places, mostly stayed within the rope line, took some selfies and played some pranks. Nobody was ripped apart with bare hands and the pieces paraded around on a spear. But they spoke as if they were storming the Bastille—and now they are being punished as if they were trying to storm the Bastille. God doesn’t like it when you play pretend.

Yet even these revolts of pure chaos gradually evolve into monarchies. The Paris mob evolves through Robespierre to Napoleon; the Boston mob evolves through Samuel Adams and James Otis to George Washington and Alexander Hamilton. And of course, in Petersburg Lenin is master of the mob almost from day one.

Therefore, “democratic energy installs a monarch” is a description of all revolutions—at least, all internal revolutions. It is unfortunate that our Eastern example falls apart here: the western edge of the old Imperium was just ceded to the Western oligarchy, like Pergamum giving herself to Rome; and her eastern rump fell into some chaos and confusion, before resolving somewhat later to a rather imperfect monarchy.

But when we pull the camera way, way back, we see clearly that the only way out of our present unlivable situation is “democratic energy installs a monarch.” Which is exactly how we got Hitler, Stalin and Mao. This is why keeping us worried about a new edition of Hitler, Stalin or Mao is exactly what keeps the 20th-century regime in power—and it is exactly why defending or reinventing these ghosts is so tempting to its enemies.

We’ve seen why a low-energy revolution has to be different from a high-energy one. But what about the resulting monarchy? A monarch still needs to keep the confidence of the people—but the monarchy’s execution cannot not rely on democratic energy. Not when there isn’t any.

The low-energy monarchy

A newborn monarchy is indistinguishable from a “dictatorship” in the modern sense. But the modern sense conceals an ambiguity, one well expressed in the original Roman definition—which, until Caesar named himself “dictator for life,” was a temporary job.

A permanent dictator would be a king, or in Latin rex. There was no word more loathed by Romans—but a king in fact was what Rome needed. Or at least what she got. Few of us realize that “emperor” was born as a euphemism for “king.”

Most but not all 20th-century dictators came into power by promising a temporary regime: an emergency reconstruction of the regime, not a regime change at all. Never say never, but this is almost always a mistake. Sovereignty with an expiration date is weak and unstable sovereignty—which can easily be worse than no sovereignty at all.

Hitler did not promise to restore Weimar. But even Hitler was not really quite clear on what would happen when a Fuehrer ascended to Valhalla. Hitler didn’t have any heirs to give his job to, of course, because Hitler was gay^H^H^H married to his country.

Of course, no empire lasts forever. But every regime should plan on lasting forever. Otherwise, it just makes its enemies think about how to outlast it.

A regime which can only take power by conceding the promise to relinquish it is in a very delicate spot. If this promise is sincere, it is stupid—not just for the regime, but also for the unfortunate nation doomed to be oppressed by “the justice of the mouse.” But to break a promise of such moment is a foul act, poisoning everything around it, which will resonate for decades as an unredeemed betrayal.

Both this instability, and this betrayal, are tremendous amplifiers of the population’s political potential. As a monarch, while you may have used democracy to get your job, it remains a potential enemy. Anything that gives potential enemies oxygen is still bad; anything that gives you oxygen is still good. Absolute power repeals no laws of power.

Still—let’s look on the bright side. The political formula of the 20th century assures you that any form of monarchy in the modern world will face enormous democratic opposition. Nothing could be farther from the truth.

Any form of monarchy in the modern world will face enormous oligarchic opposition. This is why no form of monarchy in the modern world can succeed anywhere, except here. Only an American monarchy has a way to win in this conflict—because the only way to win is to use monarchical power to dissolve the institutions of oligarchy.

The ruling class literally cannot rule without these institutions. It cannot tell anyone, or even tell itself, what to do or what to think. The ruling class has also been selected by its attraction to power—and its willingness to humiliate itself by always agreeing with power. What will it do when it has no power to agree with?

Simple: it will agree with the new power in town. Power’s pod-people act as if their brains were controlled by a radio chip tuned to a preset channel. This is not at all the case. The chip just tunes to the strongest transmitter it can hear. If their channel goes off the air, and your channel comes on, they are your pod-people now.

These exact same people would be Nazis, Stalinists or Maoists as needed. They will serve any real power just as diligently—provided it is really the strongest one around. While no sane postmodern regime would dabble in these kinds of stale old modern chestnuts, they could be just as devoted to the white race as they are to social justice.

This is why the revolution has to happen in America. When other countries dissolve their globalist institutions, they prove only that these branch offices were unnecessary. Their globalist ruling classes—biologically native, culturally American—will just tune their radio chips to New York, Washington, LA and London.

There does not have to be a globalist university in Hungary, for instance, for young Hungarians to know that New York is the Big Apple, and Budapest is not. Any writer in Hungary knows that any writer who is published in New York is more important than any who isn’t. No leader of Hungary can touch these institutions, or do anything about their power—short of partitioning the Internet, like North Korea.

But a leader of America will have no trouble in destroying its prestigious institutions—without harming a hair on the heads of their employees. America knows exactly how to shut down an institution: you lock the doors, pay the employees severance, and sell off the buildings and other assets. It is not like storming the Bastille at all.

The new regime should even be able to give the old rulers a better life. Why not? Did they do something wrong? I mean, if we’re rehabilitating Hitler here—or at least, exorcising his magical power—God help us if we are unready to rehabilitate the libs.

Whose only crime was being too innocent. Even if they were actually “in the loop,” they were only serving Moloch; even if they served his majesty passionately, they were only serving him with the passion of an addict; rehabilitation, in fact, is just what they need—their recovery will be a true political rehab. And they will never again matter.

And as for the idea of them resisting the new regime in the streets—perhaps building barricades, like the Paris Commune—it is to laugh. The Wide Awakes are not in the building. Some people do like to dress up and play in the streets—right and left, they could all be rounded up in fifteen minutes. Once a king, always a king.

Of course, after many decades of prudent monarchy, a healthy population will recover its ancient vigor and virtue—and its political energy. Someone can handle that then. Or not—after all, no empire is forever.

A civilized monarchy

Hume, perhaps the best of the Enlightenment before it turned into the Revolution—and perhaps the last major philosopher who could consider this question under any kind of freedom—defined his ideal regime as a civilized monarchy:

In a civilized monarchy, the prince alone is unrestrained in the exercise of his authority, and possesses alone a power, which is not bounded by any thing but custom, example, and the sense of his own interest.

Every minister or magistrate, however eminent, must submit to the general laws, which govern the whole society; and must exert the authority delegated to him, after the manner which is prescribed. The people depend on none but their sovereign, for the security of their property. He is so far removed from them, and is so much exempt from private jealousies or interests, that this dependence is scarcely felt.

And thus a species of government arises, to which, in a high political rant, we may give the name of Tyranny, but which, by a just and prudent administration, may afford tolerable security to the people, and may answer most of the ends of political society.

Seems like we’ve been in a “high political rant” for… some time now. Hume would define the monarchies of Hitler, Stalin and Mao as barbarous monarchies, which

know no other secret or policy, than that of entrusting unlimited powers to every governor or magistrate, and subdividing the people into so many classes and orders of slavery. From such a situation no improvement can ever be expected in the sciences, in the liberal arts, in laws, and scarcely in the manual arts and manufactures.

Do Nazi jets and rockets refute Hume? Discuss.

He goes on to compare the virtues of monarchies and republics (at this time the only pure republics in Europe were Switzerland and Holland; Britain was… a special case):

But though in a civilized monarchy, as well as in a republic, the people have security for the enjoyment of their property; yet in both these forms of government, those who possess the supreme authority have the disposal of many honours and advantages, which excite the ambition and avarice of mankind.

The only difference is that, in a republic, the candidates for office must look downwards, to gain the suffrages of the people; in a monarchy, they must turn their attention upwards, to court the good graces and favour of the great. To be successful in the former way, it is necessary for a man to make himself useful, by his industry, capacity, or knowledge. To be prosperous in the latter way, it is requisite for him to render himself agreeable by his wit, complaisance or civility.

A strong genius succeeds best in republics; a refined taste in monarchies. And consequently the sciences are the more natural growth of the one, and the polite arts of the other.

Not to mention that monarchies, receiving their chief stability from a superstitious reverence to priests and princes, have commonly abridged the liberty of reasoning, with regard to religion and politics, and consequently metaphysics and morals. All these form the most considerable branches of science. Mathematics and natural philosophy, which only remain, are not half so valuable.

It will be seen at a glance, that our system of government, that is oligarchy, elegantly combines the vices of Mr. Hume’s monarchies and his republics, with little or no sign of the virtues of either. But in mathematics and natural philosophy, not to mention the manual arts and manufactures, it remains quite strong. With what result, we see.

A hard king is good to find

Another of the myths of democracy is that a good king is hard to find.

It is cheerfully admitted by everyone that a “benevolent dictator” is the best form of government. We are all Humeans, after all… then they checkmate you! How do you find your benevolent dictator? And make sure he stays benevolent? Huh?

I don’t know, dog—how do you make sure the Pentagon stays benevolent? How do you make sure Harvard stays benevolent? Of such Jedi mind tricks is every regime made.

The reality is that a “dictator” is just a sovereign CEO. And anything bigger than your house is going to be a hell of a mess unless it has a CEO—or if it has a weak CEO. (Former weak CEO here—I make a terrible CEO. But I give good advice—usually.)

And Washington is a hell of a mess. Maybe both the problem and the solution are just obvious? Has anyone considered this possibility? In all our hard, painful wanderings in the political wilderness, in our two-and-a-half-century revolution, are we stumbling in circles in the snow, a half-mile from the Ritz? How would that look in retrospect? Pretty funny, in fact—from inside that huge marble tub, with the jets turned up high. That’s how I expect the next civilized monarchy to feel. At least at first.

In actual fact, there are a lot of CEOs in the world. And CEOing is a pretty fungible business. Sure: it helps to be an expert in something your company does. It’s not even necessary, and you can’t be an expert in everything.

Need a king? Draft one. How many Fortune 500 CEOs are under 50? More than two. Just pick one at random. You could do better, but he’ll do fine. He may not be a genius; he is almost certainly not a maniac. If he is, you can tell at a glance. So can anyone else, which is why it’s so unlikely.

Because he didn’t get his job the way Hitler, Stalin and Mao got theirs; he got it in the Humean way, by being useful. By achieving a stunning 20% year-over-year top-line growth at America’s oldest lawn-supply company, or something. Perfect! He’s hired. Again: you could almost certainly do better. But if you’re worried about doing worse…

Backup layers

A monarchy is not a temporary dictatorship. Therefore, a monarchy needs some design for accountability and succession which can render its constitution permanent. We may start our new Antonine Age with this young, excellent Lawn-King; but all kings age.

Accountability and succession are generally inseparable. As you get older, awful, awful things will happen to your brain. You can’t be expected to diagnose them yourself, too.

So a well-designed monarchy tends to include one or more backup layers which can replace the monarch in case of death or incompetence. For example, in the English joint-stock company tradition, the board of directors can replace the CEO, and the shareholders can replace the board.

Like many safety measures, backup layers introduce their own risk. The danger is that the backup layer becomes the actual regime. By definition, no force (except a second backup layer) can stop it from doing so.

A good backup layer is both internally and externally secure. Neither its own internal psychology, nor any external pressure, can deflect it from the conscientious execution of its duties.

Power corrupts. The only way to keep the backup layer from being corrupted by its own power is to make it taste as little power as possible. Once the board is micromanaging the CEO, it might as well be the CEO. As long as true accountability is maintained, the less they know about the company, the better. A backup layer that only needs to act every decade or two is fairly well protected from power’s seductions.

The backup layer must also be externally secure—since any force that can capture it, whether by coercion or seduction, can also seize power through it.

Let’s look at four possible designs for a 21st-century monarchy, each with a different approach to accountability and succession.

Perfect continuity

The simplest way to get from here to monarchy is much the same way FDR did it: to change the real form of government, while maintaining the symbolic constitution. FDR’s monarchy decayed into our oligarchy; let’s improve his design.

Perfect continuity maintains the unstained legitimacy of our 18th-century Constitution, while turning the United States into a civilized absolute monarchy.

The new Imperial Presidency has unilateral control of the executive branch. Congress is a rubber stamp. The Supreme Court gets packed every time it issues a ruling the President doesn’t like. States are kept in line by pinching their financial air supply. This version of American monarchy is very legal and very cool—just as the Roman Empire never admitted that it was anything different from the Republic.

One way to build two backup layers into this de facto regime change is to make the CEO not the President, but the VP. In this analogy, the President is the board; the voters are the shareholders.

The President gets to be a ceremonial monarch, as he is now; the VP is the boss of the Deep State. If all goes well, the VP steps up to the top role in eight years, and chooses a new national CEO for the bottom of the ticket. This is a very natural design for a one-party state; it is not dissimilar to the old PRI system in Mexico; it could work quite well with the “emerging Democratic majority,” perhaps after some kind of split between politicians and bureaucrats.

This structure would be like FDR’s White House if Harry Hopkins had been the VP—in fact, FDR only chose rubes, clowns and dimwits for this role—perhaps on account of having been through an assassination attempt. But FDR was very much a hands-off manager—whereas anyone in DC disobeyed Hopkins at his peril.

The chief problem with full continuity is that, to maintain its permanence, this regime needs to maintain permanent control over public opinion. While this is a solvable problem, the solution leads straight back to the sort of psychological-warfare toolkit that is tormenting us all today.

Hume, a man of the Enlightenment, was well aware of the humiliations of living in the spiritual handcuffs of “princes and priests.” It would be well indeed to not have to engage in this kind of priestcraft—to adopt the approach of Frederick the Great toward public opinion and free speech: “they say what they want; I do what I want.”

Full neocameralism

Using democratic elections as a backup layer is not a good engineering idea if it can be helped, because the security of this backup layer is weak—whole populations are quite easily seduced by objectively terrible ideas. Also, while the population as a whole does not have a conflict of interest with the regime, many parts of it have such conflicts.

So elections tend to focus on resolving conflicts of interest between competing groups. This is how your backup layer starts to catch fire and turn into a civil war, which is roughly the “rapid unscheduled disassembly” of political engineering.

If this same authority is transferred from the population of the country, voting by head, to the creditors of the country, voting by dollar—these conflicts of interest disappear. The reason a corporation is run by its stockholders is that they have the greatest interest in its success—greater even than that of its bondholders, whose outcome is only binary. And every shareholder has the exact same interest.

Neocameralism, the idea of porting the joint-stock company to the sovereign layer, is a futuristic subspecies of monarchy which has never been tried. It implies all kinds of daring parallel inventions. To have stockholders, you need to have stock; to have stock, you have to have profits, or at least project profits; what does it mean for a government to be profitable? We can’t quite say. But in theory, it should work.

Especially appealing is the fact that the incentive of a profitable company is also the incentive of a civilized monarchy: not just to spit out dividends, but to protect and grow the assets. The assets of a monarchy are the land and the people; so the incentive of a monarchy is to preserve and improve the land and the people. Which sounds a lot like protecting and growing the assets.

A blindingly perfect equation—in theory. Of course, the 20th century taught us a lot about blindingly perfect equations. If you try it, kids—don’t fuck it up. People will blame me, when they should be blaming you.

The anonymous trustees

Arguably, Tolkien encoded all kinds of cool political ideas into his novels. While for some reason everyone always focuses on the One Ring, really the most interesting are the Three Rings—if I recall correctly, Argle, Bargle, and Chuzz—which the Elves get their greedy little elf-paws on.

The way Argle, Bargle and Chuzz work is that they are passed from hand to hand, or rather paw to paw, and no one knows who has them. We don’t even know what they do, in fact, which leaves us free to speculate. But maybe any two of them can elect the next Mayor of Rivendell. These secret ringbearers are anonymous trustees.

Obviously, this design can be implemented in one of two ways: (a) magic; or (b) on the blockchain. Even if Argle, Bargle and Chuzz are NFTs, though, they still should be physically encoded in a durable, tamper-resistant object—they shouldn’t be duplicated.

For internal security, this anonymous board depends on the integrity of a small, well-chosen group of people, and their self-selected successors. For external security, it depends on secrecy and cryptography.

Three is a pretty small number of trustees. Thirteen might work better. Elves don’t get old, of course, but we humans do. When you have an elf-ring, keep it in a safe-deposit box with a note saying who gets it next, and tell your lawyer about it.

No one, not even the other trustees, should know who the trustees are. If their names leak, they can be pressured in the real world. If their names leak, they need to find another elf they trust, and fast.

Yet as Argle, Bargle and Chuzz, they are free to chat in their secret Slack about how the Mayor is doing. Moreover, if this constitution is built on cryptography rather than magic, their power can be enforceable—the board can install a slock.it digital lock on Rivendell’s front door, and maybe even stick permissive action links on the elf-barons’ magic swords. So only the official, ring-approved Mayor can physically rule.

Yes: this is an even more novel design than neocameralism. It’s not even futuristic. It’s super futuristic. So don’t fuck it up, etc.

The neo-hereditary monarchy

Our last example isn’t modern at all. It’s an ancient classic, with a twist.

In a hereditary monarchy, the backup layer is the royal family. Not only does the monarch bear a warm and natural affection toward his own family—if he has to be replaced, his family can not only make the call, but supply the replacement. While always dicey, this logic did get the Dark Ages most of the way to modern Europe.

The big hiccup is biology. All kinds of great dynasties have been interrupted and thrown into chaos by weak monarchs, underaged monarchs, insane monarchs… a monarch is a part, a widget, a physical component; everyone acknowledges that, if this component is perfect, monarchy itself is perfect; yet frustrating nature, always eager for drama, simply refuses us a consistent stream of biologically-perfect monarchs.

Nature is a bitch. But since monarchy was last in fashion, we’ve learned a lot about biology. Not all babies, even all normal babies, are born uniform—and a monarch is a part, a widget, a component. Using the latest widget-making technology, we can generate a steady stream of near-perfect components.

Why find kings, when you can make kings? With 20th-century artificial-reproduction technology, we can build a whole factory of kings—raising whole cohorts of princes, perhaps 10 or 20 in a batch, with each batch a decade apart. One king of each batch will rule for a decade; former kings will be influential advisors; the rest of the batch will have to be ordinary (but amazing) people.

Needless to say, education, training and selection will be unimaginably exacting to the point of brutality—even losing a prince or two is no big deal. They are only human parts, like a camshaft; the human cost of any such attrition is negligible next to the human cost of a low-quality king.

Historically, the closest design to this is the Ottoman Imperial Harem, which was also a form of open succession—designed to produce a contest among many high-quality heirs. Like many Ottoman institutions, this design had many virtues and many flaws.

Its main flaw was that there were no rules for this contest. So it inevitably turned into civil war. While there is a case for this approach, it would not resonate well with the postmodern ear. It is much better to raise the princes quasi-institutionally—and best of all to separate them from their biological mothers, who caused much trouble in Ottoman politics. Egg donation, surrogate gestation, childcare and education are four very different specialties—and no one can do all four at a consistent top level. The only problem with this science-fiction upbringing is that it seriously challenges the normal idea of family—but that is just another science-fiction problem for tomorrow to solve.

Conclusion

Which of these designs reminds us most of Hitler, Stalin and Mao? Clearly, the first—Hitler even seized power by winning an election.

I think history will reveal Hitler as a far smaller man than the legend we see today. He was hurled to the top of, then sucked under, waves he never remotely understood. It was those waves—the inevitable turbulence of the modernization of the world—that allowed the deranged and murderous revolutionary ideologies of the century to grow. Never blame the bacterium; always blame the medium. In the end, I think the Beatles will end up mattering more.

Still less should we blame the institution of civilized monarchy, three thousand years older than the “Thousand-Year Reich”—which should not make us think of Hitler, Stalin and Mao; but rather, of Elizabeth I, Louis XIV, Napoleon and Augustus.

Restoring this old form, at its best rather than its worst, is the only conceivable escape from the utter shitshow we are doomed to otherwise forever inhabit. The longer we allow the ghosts of the 20th century to fester, the harder it is to free ourselves of them. We are not here to praise them; but the public health requires that we bury them.

The first form of monarchy is also the weakest and the least stable—and, by far, the most accessible from where we are now. Yet in our low-energy age, it could even work. (My own favorite is the anonymous trustees; but I am biased, of course.)

And surely, if I can think of four, others can think of many more. And even if they’re not perfect… do you want to live this way? Do we have to live this way?

Of course, the last but most important thing every newborn monarchy needs is a plan. That’s the main work product of this book-in-progress—so stick around, dog:

Where did my morning just go? Best 10 bucks I've ever spent, better to say invested.

A Gray Mirror University would be welcome.

Nothing more to add but the Iranian revolution is a revolution you don't ever seen to reference. Although I'm working through your back catalogue.

I like neo-hereditary but I oppose the dehumanizing effects of modern birthing programs (not in a small part because of my catholicism).

I would not want to compromise the dignity of a human person, especially the monarch. However, i think it could work if we set up some sort of Bene-Gesserite breeding program for the royal family. This would be humane and dignified, like creating a prized race horse rather than artificial human soup.

After just a generation or two we would have enough swappable, competent princes, that the monarchy could essentially continue on forever. It also gets more robust as time goes on.