The golden age of informal securities

"A disturbing discovery that offers plenty of answers, but no solutions."

Figuring out that the whole centuries-old Anglo-American financial operating system is deeply broken and cannot, by any means short of a military coup, be repaired, is like being an 11-year-old and figuring out that your parents are alcoholics: a disturbing discovery that offers plenty of answers, but no solutions.

Larry Summers, god-emeritus of the Treasury, has some answers. He says:

In general, bank accounting probably doesn’t fully capture some of the risks associated with this pattern of borrowing short and lending long.

You don’t say? Dr. Summers could try reading my 15-year-old blogpost, or even this 80-year-old book. He is probably a little busy for blogposts and books, though. Sad. Note to Big Larry: borrowing short and lending long (maturity transformation) is what an Anglo-American bank does. And has been doing for 300 years and change. And in that time, there have been… a number of crises. The last one, they tell us, has happened.

A very cogent explanation of the banking crisis by a professional true believer is this Patrick McKenzie essay. See also his essay on “deposit insurance,” from last summer, which ends:

It is difficult to overstate how important [deposit insurance] is. You rely on it to the same degree as you do electricity, running water, and stable Internet connections. Like much infrastructure, it is so good you’ll hopefully never even have to realize it is there.

Hopefully! Well, we have not had a systemic banking crisis in over 15 years. Imagine if nuclear power had this kind of safety record, and “vanishingly few nuclear accidents” just meant, like, you couldn’t enter the whole state of Oregon for the next half-century.

It’s fine! It’s just one state! Everything is fine! You may never see Oregon—but your kids could! Besides, what is there to see in Oregon? And don’t you like electricity? Huh?

The mentality of Boxer in Animal Farm is everywhere. Ultimately, as Maistre wrote in his treatment of the French Revolution, “every man is convinced that he is being well governed, so long as he himself is not being killed.”

Our ancient ramshackle financial system is just one shard of our ancient ramshackle governance system. If like many Gray Mirror readers you are a programmer, think of it as an ancient codebase. McKenzie, a programmer, thinks about finance the way most people do: in the language of the ancient program. Because this program is absurdly complex and breaks every five minutes, McKenzie’s explanation is absurdly complex and his assurances break in nine months.

There is one tiny picture of a different world in his essay. This world horrifies him:

Banks engage in maturity transformation, in “borrowing short and lending long.” Deposits are short-term liabilities of the bank; while time-locked deposits exist, broadly users can ask for them back on demand. Most assets of a bank, the loans or securities portfolio, have a much longer duration.

Society depends on this mismatch existing. It must exist somewhere. The alternative is a much poorer and riskier world.

In a free-market financial system, interest rates would be set by supply and demand. In this hypothetical system, which has existed in the past but does not exist anywhere today, every borrower has an equal and opposite lender. If you want to borrow money for 30 years, find someone who wants to lend money for 30 years.

This design is stable because, borrowing genuine and exogenous cataclysms (asteroid strike, pandemic, etc), neither the demand for, nor the supply of, loanable funds, has any reason to change rapidly. Anything that cannot change rapidly is stable. Duh.

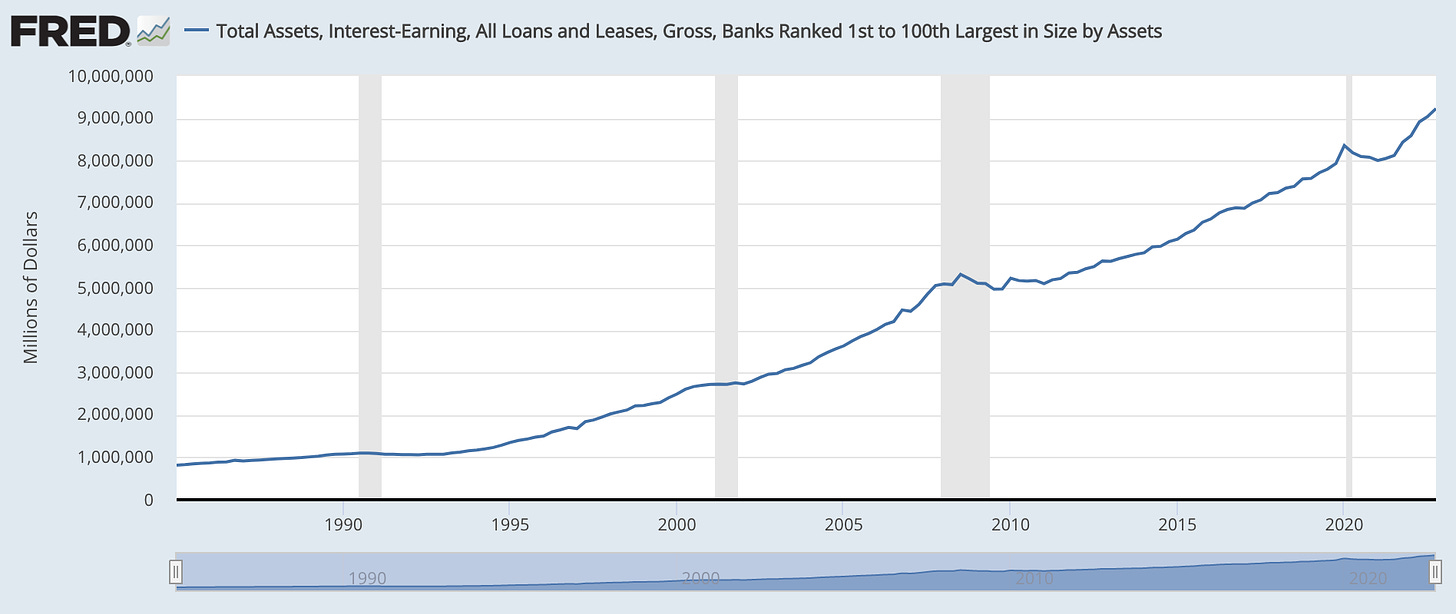

That would be capitalism. This is not how our financial system works. Our financial system is powered by continuously increasing systemic debt which is never repaid:

What this graph means is that the whole economy chronically loses money. Notice those moments where debt goes flat or even down? These are called “recessions.” When any system, big or small, goes tits up unless it can keep borrowing, it is losing money.

What McKenzie means by “poorer and riskier” is that if you take any money-losing machine, big or small, and you stop lending to it, it explodes. If you don’t want to (a) kick the can down the road by borrowing more, and (b) you don’t want the can to explode, you have to (c) restructure it. But try restructuring a whole economy without a military coup—or any other source of total power.

You might say that technology has improved a lot since 1985. So there should be a lot more debt. Because we have faster computers and sharper TVs. Take a moment to think about whether this makes sense. Take another moment to think about how long you spent just assuming it made sense. “Growth.” Think about that word—“growth.” What does it mean—besides, of course, a tumor?

In capitalism, the amount of debt an economy carries should depend on its capital base, ie, the amount of future production that has to be paid for in the present—by building things that cost in the present, but produce in the future. Like factories. Since we so rationally moved all our factories to China, finding it more pleasurable to live by consuming in the present, we Americans should be carrying less and less debt. Hm.

As for houses—are our houses getting bigger and nicer? At the rate they are getting more and more expensive? If every 30-year mortgage needed to be lent by a 30-year saver (perhaps a new graduate saving for retirement), resulting in a 10% interest rate for 30-year money, maybe… housing prices would be a little lower? Supply, demand…

But this is in a fantasy world of true capitalism which we simply can’t get to from here—not without somehow using $5T of actual dollars to repay $125T of financial assets. Which would involve a certain amount of… repricing. Of… everything.

Yes, the free market could do this. If you wanted the free market to do this, you could. “Poorer and riskier” would be a slight understatement. I am more given to hyperbole than Patrick McKenzie—I might have written “cannibal zombies walking the streets.” You can’t get there from here. Not in any way you would want to.

So it is true that society depends on “maturity transformation existing”—not because MT is good, but just because there is no safe and easy way to turn it off.

But what is the easiest safe way? And what is the easiest way to at least think about it?

How to think about fiat currency and deposit insurance

Modeling banks as “private companies” and “deposit insurance” as insurance is like modeling the sun as going around the earth: it actually kind of works. You can even predict eclipses with a purely geocentric astronomy. It takes a ton of epicycles—as you can see by reading the McKenzie posts. Why not a simpler model?

A “heliocentric” model of fiat currency starts by defining fiat currency as state equity. A “Federal Reserve Note” is a share of stock in the government. The relationship between Microsoft and MSFT common stock is the same as the relationship between the USG and FRNs: Microsoft can create and destroy all the shares it wants, and an MSFT share entitles you only to equal treatment to all other MSFT shareholders (“equity”).

When you pay your taxes (note that the heliocentric model also neatly explains MMT), you are returning USG shares to the USG to be destroyed. When the Fed pays interest on reserves, this is a dividend—Microsoft does not pay dividends in Microsoft shares, but it easily could. (Note the case of TNB—it’s not what you might think, you swine.)

We then unify Fed and Treasury, which are both organs of the USG. This allows us to model Treasury bonds (technically, bond coupons) as restricted stock—many Microsoft employees are paid in MSFT shares which are invalid until some vesting date. This corresponds exactly to a future bond payment.

Now to banking. When you “deposit” (note the Orwellian language) $1000 in Wells Fargo, you are lending 1000 FRNs to Wells Fargo, in a zero-term auto-renewing loan. Every millisecond, you lend a thousand dollars to the bank, due the next millisecond. If you don’t “withdraw” your money in the next millisecond, you lend it to WF again.

Another way to say this is that you give WF 1000 FRNs, in exchange for 1000 “WF-FRNs,” which WF promises to redeem for actual FRNs. The value of one WF-FRN is at most one FRN—discounted by the nonzero probability that WF will fail.

The trouble with this design is that “depositing” is a money-losing transaction, since the value of an WF-FRN is always less than the value of an FRN. The exact value of a WF-FRN is the value of an FRN, minus the value of a credit default swap (CDS) on WF.

But since the USG can create infinite FRNs, just as Microsoft can create infinite MSFT shares, the USG can create infinite CDS that pay off in FRNs.

Therefore, “deposit insurance” means the USG, loving Wells Fargo as it does, gives you an extra security whenever you lend money to Wells Fargo. Wells Fargo gives you a WF-FRN, and the USG gives you a WF-CDS. One WF-FRN plus one WF-CDS has exactly the value of one FRN. “Deposit” away!

But wait! Since WF is an SIB, you can “deposit” any amount of FRNs “in” Wells Fargo. But First Republic is not an SIB! So when you lend your FRNs to FR, you only get up to $250,000 of FR-CDS. Above that number—better to redeem your naked FR-FRNs for actual FRNs, then lend them to WF, for fully protected WF-FRN/WF-CDS pairs. This is a strictly profitable transaction—so everyone should do it.

But wait! Silicon Valley Bank was not an SIB. Yet everyone was assuming it would work like an SIB—and it did work like an SIB. It turned out that if you had $500K “in” SVB, you had 500,000 SVB-FRNs, 250,000 SVB-CDS, and—250,000 SVB-iCDS.

We have found our informal securities. On paper, the SVB-iCDS did not exist. But thousands of competent professionals and billions of dollars acted as if they did. Surprise: they did exist. Were you surprised? I wasn’t surprised.

The USG’s commitment to these informal securities—both to their existence, and to their informality—is rock-solid. Let’s go to the tape. Senator Lankford of Oklahoma asks Treasury Secretary Yellen:

Will the deposits in every community bank in Oklahoma, regardless of their size, be fully insured now? Regardless of the size of the deposit, will they get the same treatment that SVB just got?

Secretary Yellen responds:

A bank only gets that treatment if a majority of the FDIC board, a supermajority of the Fed board, and I in consultation with the President determine that the failure to protect uninsured depositors would create systemic risk.

Thus if you have $500000 “in” the Bank of Oklahoma, you have 500,000 BO-FRNs, 250,000 BO-CDS, and 250,000 BO-iCDS—an informal security which depends on what Secretary Yellen and other dignitaries had for breakfast. This, ladies and gentlemen, is Third World finance—an extralegal property right. Hernando de Soto, call your office.

It’s actually way worse than this. Even with Wells Fargo, you don’t actually get a WF-CDS issued by the USG. Your CDS is issued by something called “FDIC,” which is either a government agency or a private company—no one is quite sure. So for your $500K deposit in Wells Fargo, you get 500,000 WF-FRNs and 500,000 WF-FDIC-CDS.

FDIC, unlike the Fed, cannot issue FRNs. And it has written trillions of FDIC-CDS—but it only has billions of FRNs. What happens if FDIC runs out of FRNs? Do all the FDIC-CDS expire worthless? By definition, they do—but…

Of course, FDIC is backed informally by the Fed. It’s the same F, after all! So actually, when you “deposit” “$500,000” with Wells Fargo, you are actually trading 500,000 FRNs for 500,000 WF-FRNs, 500,000 WF-FDIC-CDS, and 500,000 FDIC-iCDS. Whose value exactly equals 500,000 FRNs! And the world is saved. “Press F to pay respects.”

But if we are to take Secretary Yellen at her word, an FDIC-iCDS (a rock-solid, good as gold, informal security) is worth more than a BO-iCDS (which depends on what the Secretary had for breakfast). Therefore, logic suggests that the people of Oklahoma should move their “deposits” out of the Bank of Oklahoma and into Wells Fargo.

Senator Lankford, obviously well-briefed, asks exactly that question:

What is your plan to keep large depositors from moving their deposits out of community banks into the big banks? I’m concerned you’re about to accelerate that by encouraging anyone who has a large deposit in a community bank to say we’re not going to make you whole, but if you go to one of our preferred banks we are going to make you whole.

Ms. Yellen’s extremely reassuring response:

Um, look, that is certainly not something we are encouraging… we felt that there was a serious risk of contagion that could have brought down and triggered runs on many banks, um, and that something given that our judgment is that the banking system is safe and sound, um, depositors should have confidence in the system…

Extremely confidence-inducing indeed…

But once we have described this bizarre pyramid of formal and informal securities, what is the way forward? As Hernando de Soto would tell you, the solution to informal Third World property rights is one of two options: cancel, or formalize.

It’s not a choice. Canceling all these iCDS—as a strict, autistic libertarian would want—means zombies eating human flesh in the streets. Formalizing them means—things keep working the way they work now. The iCDS become CDS. The FDIC “insures” all the “deposits” “in” the Bank of Oklahoma. And the Fed formally “insures” the FDIC.

But when you look at all of these nominally “independent” corporations giving free securities to each other, like Christmas just went out of style, it still just feels wrong. What is a simpler way to keep things working the way they work now?

Well, we could just acknowledge that not only is the Fed is a government agency, and FDIC is a government agency, but the Bank of Oklahoma is also a government agency. This explains why the government (a) gives it free securities and (b) tells it what to do.

If we consolidate the whole banking system onto USG’s balance sheet, the whole system makes perfect sense. Instead of a BO-FRN plus a FDIC-BO-CDS plus an FDIC-iCDS, you just have an FRN. Which is how you think of a dollar “in” the bank—as a dollar.

As for the loans that the Bank of Oklahoma makes—they are just government loans. The government of the US, like the government of the USSR, is a state lender. This is why the government of the US has strict regulatory principles that defines who does and does not deserve a bank loan.

In the new consolidated system, lending is no longer a private-sector activity—you simply apply to the government for a loan, which uses standard criteria to deny or approve you. Which is exactly how it works when you buy a house right now. The government could even incentivize good lending through a sales-commission system, replicating the profit motive of existing banks—to the extent that regulators have left them with any lending discretion whatsoever. Which isn’t much.

This is exactly why the Fed did not approve (stop snickering) of TNB, which proposed to pay 4% interest on checking accounts by depositing the money directly in the Fed, which pays 4.65% on its reserves—and not making any loans at all. While customers would love this product, and it would be risk-free without any FDIC “insurance,” TNB would not fulfill the actual purpose of banking—to gavage the economy with debt, like a foie-gras goose. Because if the borrowing stops, the whole system explodes.

This is the infrastructure which Patrick McKenzie calls “so good you’ll hopefully never even have to realize it is there.” Well… uh… we, uh… realize it is there. Good times!

But where are we now? What has actually been done? What is going to happen?

I was puzzled in 2022—somewhat to my financial detriment—when the Fed jacked up rates from 0% to near 5%, in order to generate the fabled “soft landing” and whip inflation now. What I expected was a “hard landing.” What we got was neither—we got no landing at all.

At a very abstract level, when you pressure a system in some direction and don’t get the expected response in that direction, it suggests that the pressure has no outlet. Put a frozen palak paneer in the microwave for two minutes, after sticking a fork in the film—steam will escape. Don’t pierce the film—no steam will escape. After three minutes… there will be spinach all over the inside of your microwave.

What the absence of a landing suggests is that there are only two kinds of landing: no landing, or a crash landing. One historically recurrent tendency in financial regulation is to “stabilize” systems by disconnecting market signals, removing pressure’s outlet.

Now, this can actually work. Make a “piercing-free” palak paneer with a film that is three times as thick as usual: it will take four minutes to explode, then blow the door of your microwave. But if your Indian food is packed in some kind of plastic pressure vessel, you can microwave it for fifteen minutes, converting all the water to steam, and nothing will happen. Allow five minutes to cool and open very carefully.

Which is it this time? If you know… you can profit…