The historical guilt of the old regime

"Presidente Zod, it turns out, knows that freedom follows order."

I don’t usually respond to attacks from the mainstream, or as I prefer legitimate, press. Usually these articles are of the craven drive-by type that Steve Sailer (America’s best illegitimate journalist) calls “point and sputter.” Our ink-stained hero comes smoking in, screeches to an intellectual “California stop,” sprays a few rounds, and peels out. Our hero is not here to engage and is certainly not expecting any variety of return fire. Not only is his text worthless—it is not even worth taking to task.

Whereas one Matt McManus, no journalist but at least a professor—if a mere lecturer, a humble grove-toiler far from the seagull’s cry—writing in Commonweal—legitimate, yet still oddly Catholic—has bravely chosen to dig in and do his homework. Or what he thinks is his homework! We’ll send Dr. McManus home with more homework; no obligation, and only praise if he actually decides to do it. Which he won’t.

We have to respect this one OG who decided to stick around and find out. However, others should be “incented,” as they say in DC, to avoid similar bad choices in future.

Let’s start with some history…

The crimes of grandfathers

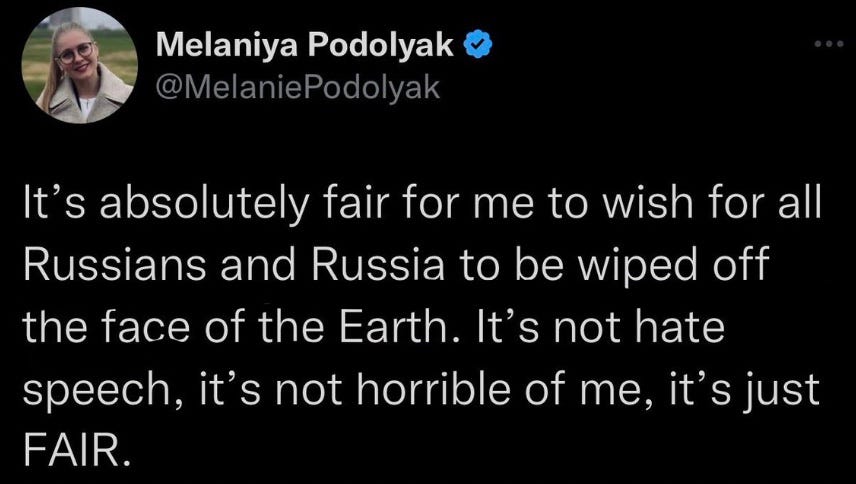

It is an incontrovertible fact about the 20th century that all 20th-century political traditions, including the American liberal and progressive tradition, traded in the politics of mass annihilation. As many still do—if you hear them talk about Russians.

Russians! How strange a thing is history. It’s 2023, and that the heirs of Pete Seeger should again “Shriek with pleasure if we show / The weasel’s tooth,” baying for guns and tanks and blood in some Dnieper meatgrinder, as eagerly as they once sang for peace and love and flowers—but against Russia of all countries—is the most delicious of history’s postmodern ironies. And the most painful. Who is shelling Donetsk?

And yet the Ukrainian abattoir, as absurd as it is tragic, is a throwback. In our century the fires of mass slaughter have burned low—perhaps from genuine spiritual advance, but perhaps from a general decline in the passion and energy of humanity. When peace is just apathy, avarice and accidie, peace is not a symptom of health. The peace of decline is the peace of death.

What is most peculiar about this fact is that when we think about mass annihilation, we think about our enemies’ campaigns of mass annihilation. True: the Holocaust may be the best-documented crime in human history. But it is their crime, not our crime. When we go looking for the spirit of redemptive Catholic thinking, or whatever, are we in the right moral place when we focus on the crimes of our enemies? Discuss.

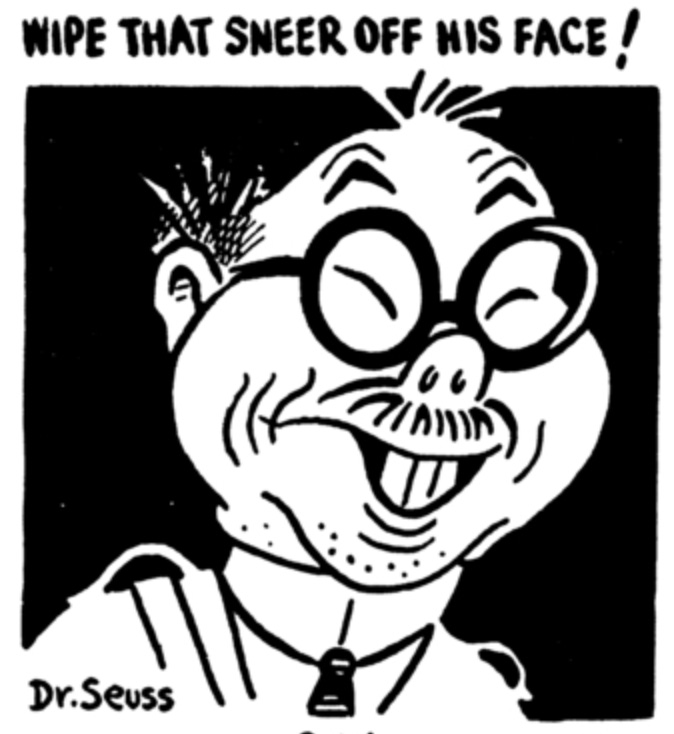

True: it is not us and them. It is our grandfathers and their grandfathers—and the idea of a national Sippenhaft is itself a gross hypocrisy. But history still matters. History is power, because narrative is power, and because the story of the present has to be told by starting from the past. Imagine an America in which every high-school junior had to sit through Hitler Lives before lunch, or read Nicholson Baker’s Human Smoke, or maybe an edition of John Hersey’s Hiroshima printed with Dr. Seuss’s war cartoons:

No history of the present in which World War II was a Marvel movie could start from any such past. (If you doubt this, you really should spend 15 minutes with Hitler Lives!) And if World War II was not a Marvel movie—how does the present even make sense?

As it happens, my own father’s parents did not participate in wiping the bucktoothed smiles off any Japanese faces. Or even cooking the faces off any Japanese schoolgirls. (Were you going to say this was necessary, though unfortunate? Just listen to yourself.) No—my grandfather fought in the Battle of the Bulge. But also, he was an American Stalinist—from the 1930s to the 1970s.

The Bolsheviks too joined the “two-comma club” in mass murder. And those who want to interpret 20th-century communism as an unfortunate, but somehow essential, defensive response to 20th-century fascism have a chronology problem to finesse. And the same is true of those who want to interpret the alliance between the US and USSR as a defensive reaction to Hitler—more on this anon. Much more.

Returning to Professor McManus—a self-described progressive and social democrat—when in the year 2023 you read the word “fascism,” a reference to a movement of our cultural enemies that was defeated 78 years ago, it is a good habit to ^F the document for “communism”—a movement of our cultural allies that was victorious 78 years ago—and wonder why it is more important to be afraid of dead devils, than living ones.

Of course Lenin’s party was literally the Social Democratic Labor Party. And of course since Teddy Roosevelt went to the great hunting grounds in the sky—that is, for about the last century—“progressive” in American discourse has just meant “communist.” My grandparents, CPUSA members whose faith never lapsed, said “progressive” for their whole lives; the Venona dispatches, messages to the KGB from US assets, use it. That kids these days have no idea what this word means does not excuse them. And it certainly does not excuse a political-science professor—or, at least, lecturer. (To be fair, young McManus has an impressive publishing record and is surely well on his way to Harvard, so long as he doesn’t use an illegal word or disrespect a protected class.)

Bernie Sanders, everyone’s favorite progressive grandpa, “honeymooned” in the USSR. Imagine if it was Hitler. “Let’s take the strengths of both systems,” Charles Lindbergh said upon completing his trip. “Let’s learn from each other.” Contrary to Jewish lies, Lindbergh’s journey was not a honeymoon… no, he was merely establishing a “sister city” relationship between St. Louis and the lovely Alpine village of Judenausrottung…

This, for we red-diaper babies and grandbabies of the Ivy League elite, is our version of what today’s good Germans call Vergangenheitsbewältigung: coming to terms with the past. Not to be overly repetitive—but that ain’t supposed to mean your enemy’s past.

Of course, the USSR of 1938 was not the USSR of 1988. Would the Third Reich of 1988 have been the Third Reich of 1938? Was the Spain of 1968 the Spain of 1938?

And if the popularity of the USSR in 1988, among the most elite American social class, was a candle, the popularity of the USSR in 1938, among the most elite American social class, would be a streetlight. A stadium light. It is hardly an exaggeration to say that in the 1930s, the “Soviet experiment” was cool among all cool people.

Professor McManus, too, is cool… even if he is a “Catholic.” In the same way. He has some coming-to-terms-with-the-past to do—if he will only do his homework.

Liberty and security

McManus starts his sneering screed with an old quote of me, clearly meant to shock:

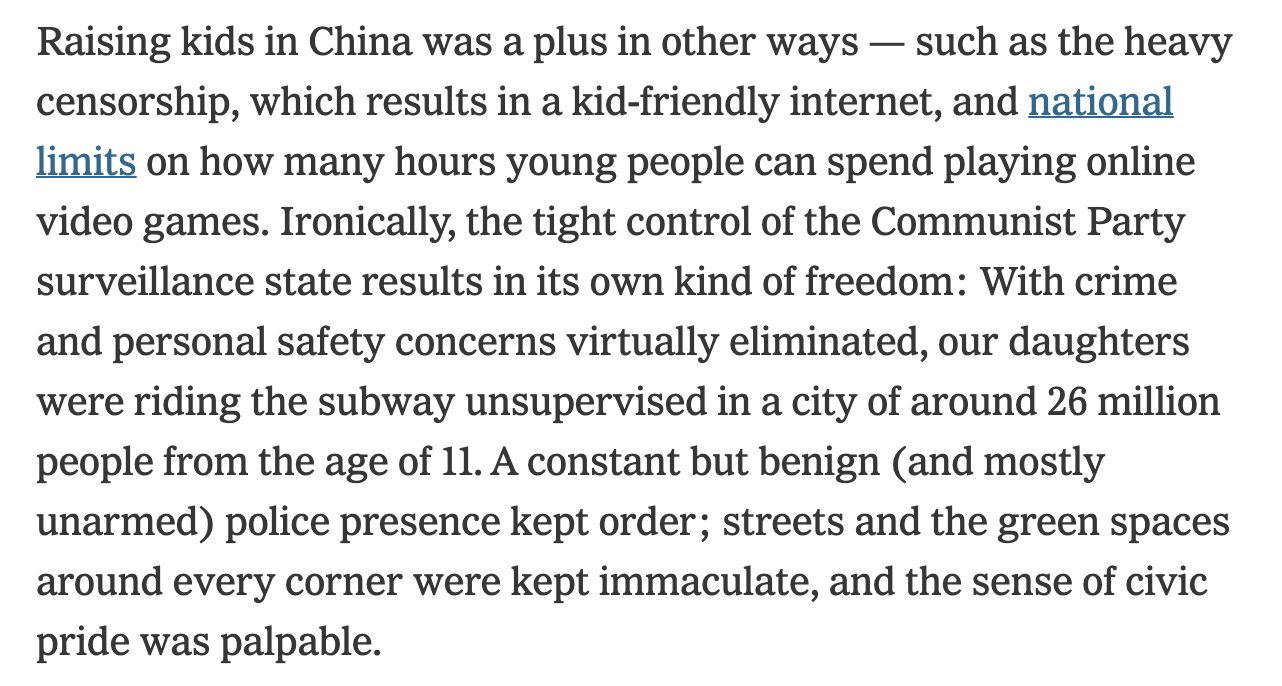

Or as the New York Times put it—just the other day, in an op-ed by an American who had raised her children in China—

McManus is already sneering at this woman. Civic pride? Who is this? What has she done? No—he doesn’t have children—he has publications—anyone can have children…

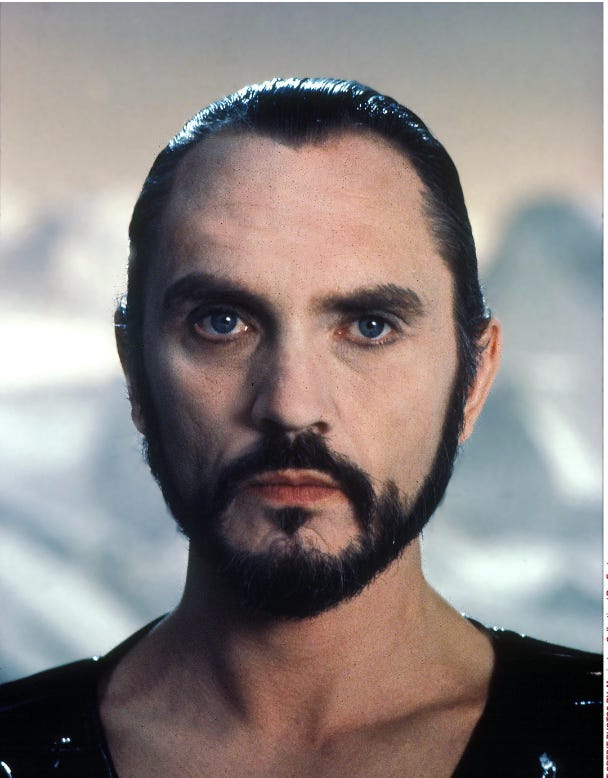

Maybe then he should take it up with Ioan Grillo, the planet’s top narco-journalist, who recently wrote about the weird miracle of El Salvador… which has somehow, without anyone noticing, fallen under the control of a Lebanese dictator who looks like General Zod with a tan:

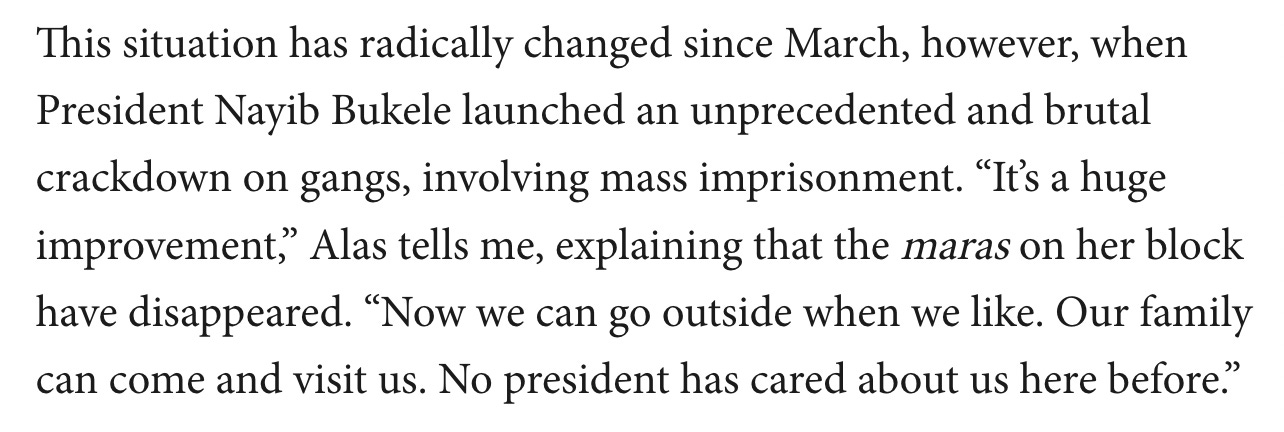

Presidente Zod, it turns out, knows that freedom follows order. Presidente Zod, by the simple policy of building gigantic prisons and filling them with all the tattooed monsters his jackbooted minions can find, has brought the Salvadoran homicide rate down by more than an order of magnitude. This is how the result looks on the street:

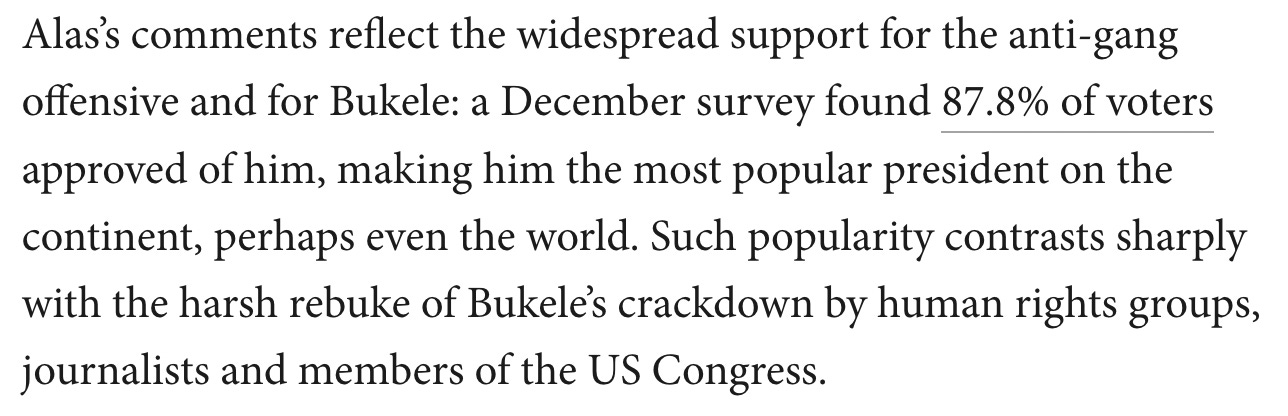

Kneel before Zod! If “now we can go outside when we like” isn’t freedom—what is? But guess who really cares—not the Presidente, but:

Colonialism much? Which side is the Professor on here—democracy, or colonialism? It sure seems like his instinct would be to go with the “human rights groups, journalists, and members of the US Congress.” And not the Salvadoran housewife.

As McManus himself scornfully reprises my position:

Yarvin sometimes writes as if his problem with the democratic Left is that it is committed to chaos. As he puts it in Gentle Introduction, “Right represents peace, order and security; left represents war, anarchy and crime.”

Indeed, and you have no further to look than Presidente Zod versus the human-rights groups to see what I meant. (Legal question: is Bukele eligible to be Presidente of San Francisco? “Fierro en guerra, oro en paz,” indeed. Venga al norte—we have such sights to show you…)

Speaking as a diplomat’s son, I will say that the global elite are genuinely some of the best people in the world. But we are not always right. And it rather displeases me to see a member of my own caviar caste sticking up for us, while he pretends to be sticking up for them. In the world I grew up in, there is no worse sin.

McManus writes in this smeary impressionistic point-and-sputter style that will toss off, absolutely without any basis or evidence, huge sweeping insinuations like

In his more candid moments, Yarvin will admit that his real priorities aren’t order and stability—at least in the near term—but protecting the freedom of an elite by imposing strict laws on the lower orders.

Strict laws on the lower orders! Such slurs reveal so much about the weird progressive mind—angry, like a leopard accosted at its prey, that it has even been challenged in its narcissistic, psychotic and destructive project of imposing chaos on the “lower orders.”

Chaos, of course, has a beauty of its own. I am sad to report that this beauty is wasted—more than wasted—on the “lower orders.” It is never wasted on the caviar caste—which, though Professor McManus probably makes like 39K, is a social class. (He may only make 29K—but he has publications. He is surely welcome at anyone’s art opening.)

How does McManus justify his position? If he had to talk to random ordinary Chinese and Salvadoran people who just like being safe, and explain to them why Premier Xi and Presidente Zod are, actually, bad, what would he say? This seems like a chance for a fascinating essay from the Professor. I think it’s our first piece of homework.

More bad history

About halfway through his essay, McManus runs out of point-and-sputter and starts just wildly smearing me for not conforming to his wildly ideological Chomskyite-Fonerite progressive history of the 20th century. I feel it’s incumbent on me to respond with as much compassion as I can muster under the situation.

It is always good to give an adversary the benefit of the doubt. And in these dark days even a history professor can be excused for not knowing that there is any other way, besides this worthless New Left mouthbreathing, to read the past. Historiography is the mother of history, and who teaches historiography? Or even knows what it is? Let’s work through some of McManus’ shallow, bilious spittle and try to sort it out.

He starts this run in the best possible way—by accusing me of not being a Chomskyite:

He dismisses C. Wright Mills and Noam Chomsky’s claim that the wealthy constitute an unaccountable political elite in the United States. The real unaccountable elite, Yarvin claims, consists of people like Chomsky himself.

How is Chomsky not elite? Who is he accountable to? Who is McManus accountable to? How is he not elite? Just by thinking logically in literal words, we can learn a lot.

I can explain how professors are powerful. How are rich people powerful? Moreover, which rich people do we mean—the “Mr. Burns” Republican caricatured rich people who are a meme that has been stale for a century, or the actual social donor class that pours giant rivers of money into progressive NGOs? If we measure the power of the rich by the political valence of their donations, we see clearly that progressivism itself is a measure of the power of money in the American regime. Has Professor McManus really never heard of the Ford Foundation? O rly? That power is not set against the professors—it is very much on their side. (Chomsky himself is an old weirdo, though his indirect influence—as we see—remains absurdly immense.)

Wading through McManus text for a coherent argument which is more than a sneer, we reach another quote of mine which he calls “simply bizarre":

It is in fact very difficult to argue that the War of Secession [his term for the American Civil War—McManus] made anyone’s life more pleasant, including that of the freed slaves. (Perhaps your best case would be for New York profiteers and Unitarian poets who produced homilies to war.) War destroyed the economy of the South. It brought poverty, disease and death.

Success has destroyed Substack and made it impossible to enter a nested blockquote. McManus responds:

He does not mention that it also brought emancipation and some measure of justice, despite the efforts of white supremacists to reassert their power through violence and anti-suffrage efforts.

I want to focus your attention, dear reader, on this conflict of visions—a conflict of costs that are concrete, like “poverty, disease and death,” and benefits that are abstract, like “emancipation and some measure of justice.”

We in the caviar caste are very big on abstractions. I like abstractions. They help me think. However, when the price of an abstraction, like “emancipation and justice,” is very high, like “poverty, disease and death,” I might start to question what I was buying. This does not appear to be an issue for Professor McManus—whose carelessness in this matter is chilling.

His homework here is to read 10 or (better) 20 randomly chosen slave narratives. In an incredibly epic act of makework for unemployed historians, the Federal Writers Project in the 1930s rounded up as many living ex-slaves as they could find and took their oral histories. So, in the 21st century, if you want to compare the life of a random slave in 1855 with the life of a random sharecropper in 1875, you have no need to ask some mouthbreathing Brooklyn Marxist. You can ask a random slave. Try it.

You may have already asked yourself similar troubling questions, like: “World War II, was it good for the Jews?” McManus sounds like an Irish name—the Troubles, were they good for the Irish? Is it way better to be ruled from Brussels, than from London? “They’re just questions, Leon.”

By the way, “War of Secession” is the European name for the war and I like it the best, because it is not a name that makes an argument—unlike the Northern or Southern names. The job of a historian is to figure out what really happened, not to beat his political enemies over the head with tendentious, emotional, juvenile propaganda. Again, though—in 2023, it’s easy to see why someone might get that impression.

Then there are the many places where Yarvin insists that the United States, from Wilson onward, handled Communism with a velvet glove. He simply dismisses the fact that Wilson sent soldiers in to crush the Bolshevik Revolution…

The Cold War is unfortunately one area in which progressive historiography is so universal that there is almost no systematic scholarship that is worth a barrel of piss. A good rule of thumb is that if your historiography of the Soviet Union matches the Soviets’ own historiography, some long-forgotten communist has urinated in your tea. This whole subplot needs to be totally revised and it’s not like there is money to do it.

The axiomatic assumption of almost all academic students of the Cold War is that there was no good reason for these revolutionary progressive powers to quarrel, and every reason for their revolutions to converge. From this starting point, they look for “hardliners” on each side who fomented this unnecessary animosity. The question of why so many fine Americans of the caviar caste were funding, protecting, and collaborating with this gigantic gang of mass murderers is seldom if ever raised.

Professor McManus’ homework is to read Wall Street and the Bolshevik Revolution, by Antony Sutton—by no means a perfect historian, but a brave one—America’s Siberian Adventure, by William Graves, commander of the Siberian intervention, which will leave him embarrassed (if the Professor is capable of embarrassment) about his appalling Leninist lie of “sent soldiers in to crush”; Raymond Robins’ Own Story, a shameless hagiography of Raymond Robins, leader of the Red Cross Mission which was an informal American embassy to the Bolsheviks, and Russia From the American Embassy, by David Francis, the official US ambassador to the Kerensky regime.

While this is a long assignment, it is a deeply rewarding journey into historiography. Among the interesting things the reader will see is the way that Graves and Robins virulently deny being on the Bolshevik side, while in fact all their objective actions favor the Bolshevik party line. Robins’ hagiographer writes of him:

He is the most anti-Bolshevik person I have ever known, in way of thought; and I have known him for seventeen years. When he says now that in his judgment the economic system of Bolshevism is morally unsound and industrially unworkable, he says only what I have heard him say in every year of our acquaintance since 1902.

This is a peculiar thing to say in a book that starts with:

With Bolshevism triumphant at Budapest and at Munich, and with a Council of Workmen’s and Soldiers’ Deputies in session at Berlin, Raymond Robins began to narrate to me his personal experiences and his observations of the dealings of the American government with Bolshevism at Petrograd and at Moscow.

But he was not merely an observer of those dealings. He was a participant in them. Month after month he acted as the unofficial representative of the American ambassador to Russia [sic—actually, he was the ambassador’s principal enemy] in conversations and negotiations with the government of Lenin. Throughout that period he saw Lenin personally three times (on average) per week [my italics].

All sources, including this book, agree that Robins was the chief American emissary to, and American promoter, of the Bolsheviks in this period. The Robins party line is that the Bolsheviks are bad, but we have to be realists and “deal” with them. This facile excuse, with its “pinprick” attack to demonstrate mandatory hostility to the Bolshevik beast, feels theatrical and perfunctory. It is found in many works of the period.

Pitirim Sorokin, a young Russian politician who fled the Revolution and became a prominent American sociologist, sees Robins in action in Moscow:

The despotic nature of the Bolsheviks’ policy became daily more apparent. After having broken up the Constitutional Assembly, while the autocratically appointed (not elected) All-Russian Conference of the Soviets held their meeting in Moscow, a meeting in which the American Red Cross Colonel, Raymond Robins, actively participated, while they were welcoming the “Power of the Peasants and Workers,” they began to break up all newly elected Soviets which in any degree resisted their tyranny…

Antony Sutton quotes a seized document:

On returning to the United States in 1918, Robins continued his efforts in behalf of the Bolsheviks. When the files of the Soviet Bureau were seized by the Lusk Committee, it was found that Robins had had “considerable correspondence” with Ludwig Martens and other members of the bureau.

One of the more interesting documents seized was a letter from Santeri Nuorteva (alias Alexander Nyberg), the first Soviet representative in the U.S., to “Comrade Cahan,” editor of the New York Daily Forward. The letter called on the party faithful to prepare the way for Raymond Robins:

Dear Comrade Cahan: It is of the utmost importance that the Socialist press set up a clamor immediately that Col. Raymond Robins, who has just returned from Russia at the head of the Red Cross Mission, should be heard from in a public report to the American people. The armed intervention danger has greatly increased. The reactionists are using the Czecho-Slovak adventure to bring about invasion. Robins has all the facts about this and about the situation in Russia generally. He takes our point of view.

In other words, like Wilson and other American progressives of the period, he ran all the interference he could for the nascent—and already bloodthirsty—USSR. From the first, Lenin and Wilson both played the Raymond Robins game of vociferously and hyperbolically and hypocritically denouncing each other. They were always genuinely competing—and they genuinely wanted to obscure their genuine collaboration.

When we dig deeply enough into history to actually figure out what really happened, not just to find facile stories to beat our enemies over the heads with, we have no choice but to grapple with these attempts at obscuring, these “set-up clamors.” Is figuring out the present easy? Sincerely figuring out the past is much, much harder.

…and jailed members of America’s socialist party.

Debs was in no way working with or associated with Lenin—though they certainly had many supporters in common.

And in case Professor McManus has somehow not noticed, vicious, often bloodthirsty factional infighting has been the hallmark of all 20th-century leftist movements. It is also true that Hitler jailed Roehm and sidelined Strasser. We do not conclude from this that the solution to radical Nazi terrorism is to support moderate Nazis.

But the best of these little tussles with the 21st-century academic consensus is over the beautiful island country of Haiti. In the 19th century, Haiti was the only part of the world that had fallen to the chaotic Third World conditions which, after 1950, became common in the former European colonies. So by reading 19th-century reactions to Haiti, we can see how the 19th century would have regarded the 20th—or at least, one important aspect of the 20th.

A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away, I wrote:

In Haiti, we see one aspect of life without promises made and kept: poverty, corruption, violence and filth. In a word: anarchy. Haiti is the product of the persistence of human anarchy, and an excellent symbol because it symbolized exactly the same thing to Carlyle and Froude. The latter visited; his observations are recorded in his travelogue of the trip, The English in the West Indies; Or, the Bow of Ulysses. Haiti is far more anarchic now than it was in 1888, of course, whose Port-au-Prince is a paradise next to today’s. Froude gets all enraged because he sees a ditch full of garbage. The 19th century’s Haiti is the 21st’s whole Third World.

McManus is not amused:

All of this is wildly misleading. Haiti was founded by heroic men and women who launched the first successful slave revolt in history.

It is amazing how even the tone of the narrative, with words like “heroic,” has become as factual as the date of a battle to this sorry excuse for a scholar. Haiti was founded by heroic men and women who launched—well, not the first—revolutionary genocide in history. As Wikipedia dryly notes:

The Haitian Revolution defeated the French army in November 1803 and the Haitian Declaration of Independence happened on January 1st 1804. From February 1804 until 22 April 1804, squads of soldiers moved from house to house throughout Haiti, torturing and killing entire families. Between 3,000 and 5,000 people were killed.

Not to worry! “Torturing and killing entire families” can be good akshually:

Nicholas Robins, Adam Jones, and Dirk Moses theorize that the executions were a “genocide of the subaltern,” in which an oppressed group uses genocidal means to destroy its oppressors.

20th-century scholarship! Never change. (Don’t worry, it won’t.) The explanations for Haiti’s failure to be Japan have shifted over the years—I feel I reached a real low this summer, when a progressive I was debating on stage insisted that what Haiti really needs, to start turning itself into Japan, is a higher minimum wage:

As a monarchist, I can tell you that Haiti could probably use Emperor Jacques back, genocide or no genocide, since it currently has no elected officials and is under the de facto control of a gang leader known as “Barbecue”—whose Wikipedia page notes:

Chérizier has denied that his nickname “Babekyou” (or “Barbecue”) came from accusations of his setting people on fire. Instead, he says it was from his mother's having been a fried chicken street vendor.

¿Porque no los dos? But the latest Haiti just-so story to grace the pages of the narrative, incredible as its chutzpah may seem, is that Haiti in 2023 looks like the above because of—the indemnity that the French made them pay for the aforesaid genocide—almost 200 years ago.

After several unsuccessful efforts to take back the island by force, the French King Charles X ordered the Haitians to pay upwards of 40 percent of their national income to former slaveholders in reparations or face further violence. Thomas Piketty estimates that the French owe the Haitians at least $28 billion from this extortion.

Professor McManus’s views, or Piketty’s for that matter, on the Treaty of Versailles, were not recorded. The Third World’s history of unpayable national debt is a long one. The world’s history of unpayable national debt is a long one.

However, if we humor the ridiculous Marxist theory that the First World has kept the Third backward through profitable extraction of colonial rents, debt payments, etc, we have to at least keep ourselves grounded by measuring the actual net payments—rather than notional amounts which not only could not be paid, but were not paid. The notional amounts in the Treaty of Versailles were pretty high, too—to say nothing of a certain indemnity to Israel—and yet Bavaria, apparently, is doing fine. It certainly doesn’t look much like the photo above.

Helpfully, Wikipedia, which is a reliable source, has this number—sourced, I believe, from the New York Times:

Over a period of about seventy years, Haiti paid 112 million francs to France, about $560 million in 2022.

These were payments on the gold standard. A French gold franc is 0.29 grams of gold; a gold dollar was 1.6 grams of gold; so this was about 20 million dollars in gold, over 70 years. 30x price inflation since the 19th century is a good rule of thumb, so $560M feels about right. (Larger numbers seem to include interest.) When I work this out in gold inflation rather than by price inflation, I get about $2B.

For a country… over 70 years… this is not a lot. Is this 19th-century debt really why Haiti does not look like Bavaria? Is Professor McManus sure about that? Are there really no other countries that had a lot of 19th-century foreign debt, yet prospered? His homework is to read The French Revolution in San Domingo, by Lothrop Stoddard, and Where Black Rules White, by Hesketh Pritchard.

Conclusion

Alas, after this fun digression into actual if mendacious history, McManus gets back into his mode of stale, windy revolutionary cliches:

But to focus on the flaws in Yarvin’s thinking is to miss the point. What has made him appealing to so many on the Right isn’t the quality of his reasoning but his undeniable ability to express reactionary ressentiment in a twenty-first-century techno-hipster vocabulary. Right-wing ressentiment combines a similar attitude of victimhood with megalomaniacal feelings of personal superiority. It takes the form of insisting that one is part of some natural elite that deserves status and power, but is persecuted by the weak and inferior who dare to demand equal status with the strong. Much of the reactionary tradition is a long series of “irritiable [sic] mental gestures” in response to the outrageous fact that, somehow, the clearly inferior keep gaining the upper hand. This is usually followed by tedious instructions on how the naturally superior can take power “back.”

By “the clearly inferior,” I take it McManus does not mean himself and his caviar-class, NPR-listening friends—but the Haitians, workers, peasants, etc, on whose behalf he toils, lecturing for far too little pay, in the academic saltmine of a freshwater college.

Over time, the grim experience of an academic serf and that of an agricultural serf seem to merge—the lecturer is a sort of sharecropper, paid with a handful of pennies, and restricted to the grim floodplain landscape of postmodern Chomsky-Fonerism. There is no biodiversity on this red-dirt farm. There is only one crop. McManus has no choice but to pick it. Imagine him agreeing with me, then trying to have a career. Even with all his fine publications, he will be lucky to make it out of Michigan. Sad! And peace begins with feeling your enemy’s pain.