The presentee election

"Every vote is cast in person by an identified citizen before an independent witness."

Why do we have elections, anyway? It’s a strange nation indeed that loves elections, but loathes politicians. We seem to regard democracy (in the literal sense of the word, meaning electing the people who run, or purportedly run, the government) as an unpleasant necessity—an odd place for a 250-year-old revolution to wind up.

The answer is actually simple. In this degenerate state of late democracy, we have elections because we’d rather not have civil wars. Each side sees our elections as its shield against the other side—which is ruthless, powerful, and bent on its destruction.

As Matthew Yglesias tweeted in 2016, “My guess is that in a Trump administration angry mobs will beat and murder Jews and people of color with impunity.” This was a centrist perspective. Yglesias, a third-generation hereditary baron of publishing with blood as blue as Maradona’s shirt, was not then involuntarily committed, but went on to become the new king of Substack, which is how we know America is a communist country: the religion of a nation is whatever collective delusion can bind her together.

Of course it is easy to see whose mobs get to beat whom with impunity. Of course, it is easy for you to see. It is easy to see because you are already outside the illusion. But it doesn’t really matter; by definition, those inside the illusion see only the illusion. We are all watching the same crappy movie, and it shows.

The American nobility really thinks the foul commoners are ready, willing and able to destroy them. I myself grew up in this fear. It was the ‘80s and Jerry Falwell was coming to get us, or something. As you move backward in the 20th century, this belief grows more and more credible—which means that as you scrub your time machine forward again, it grows less and less credible. But those inside the bubble see only the bubble.

The commoners, too, think the nobles are out to get them. This may be their only accurate perception of political reality. Though it is certainly not how we nobles think of our goals, it properly characterizes the impact of our actions. So commoners too parse the conflict as a case of collective self-defense—if less clearly and consistently.

This is the psychology of war. From here on out, elections have no other meaning. In a cold civil war, a vote is a paper bullet. Anyone still talking about “issues” is a chump.

Hence the shape of the cold civil war: two mostly-harmless sides which have reduced politics to the basic problem of self-defense. Each side makes a living by pretending to defend its supporters against the aggressions of the other. One side’s performance is unnecessary, and the other side’s is ineffective. And this is what elections are about in the 2020s, and probably for as long as they last.

And in this late and degenerate condition of democracy, fair elections are not less important—they are more important. They are all that keeps the civil war cold.

If this cold civil war can at least be kept in the realm of head-counting and out of the realm of head-chopping, everyone benefits. That’s why we invented elections. In lieu of fighting, just award the victory to whoever shows up with the mostest. Any actual fight would probably have the same result, but at much greater human cost.

The purpose of an electoral system is to make both sides trust that the winning side has more adult citizens willing to do something for it—something small, something trivial, but something.

The step from this trust to full mutual consent is a short one. It’s easy to concede when you know you’re outnumbered. It’s even easier when you know that human beings are fickle and both sides are, at least in some ways, awful—meaning the pendulum will swing back as the swing voters get a taste of their own bad medicine. Creating a sort of rough, unsatisfactory, decaying stability.

Such was the late 20th-century regime—which we are starting to see as a temporary hiatus between crises. It kind of worked, it kind of sucked; many regimes are worse and many are better; be careful what you wish for, but don’t let that stop you wishing…

But all this great reasoning only works with mutual trust in the electoral mechanism. When this trust is broken—what then?

Communication breakdown

America’s shambolic election system is now completely failing to create trust. Losers do not feel they are outnumbered; they feel they were cheated. America’s institutions are worsening this problem by insisting on a return to trust ad baculum.

Eschewing any positive measures which might mollify skeptics rational or irrational, our institutions simply add election denialism to their growing list of career-ending thoughtcrimes. Nice moves with the red saber, Luke! Don’t you love how light she feels in your hand? And this baby is the low end of the Sith line… sure, she’s expensive…

Moreover, the official public story relies on the sensible idea that subtracting a legit vote is somehow more awful than adding a bogus vote. This is what old Kenobi sounds like when he explains how you’re obviously looking for some totally different droids. Later—while your imperial supervisor is chewing you out—you so clearly remember thinking that one plus one could easily be three… why, then, should it not be three? You may go about your business…

The global perspective

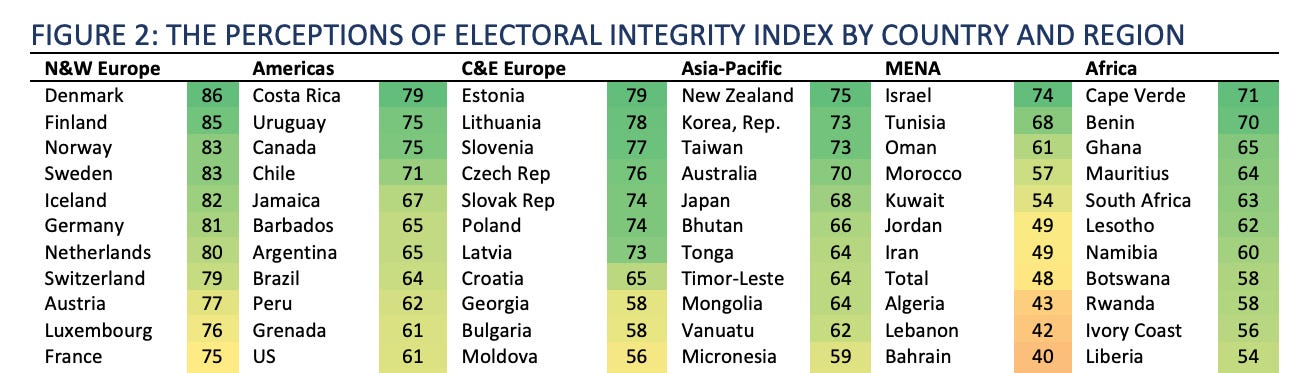

Meanwhile, the credible international authorities (by which I mean Harvard) of 2019, working from a survey of election experts, rate American election integrity behind such kings as… Peru, Mongolia, Lesotho and Tonga. But tied with Oman and Mexico:

A peek at Mexican elections, though, suggests that Mexico may want to challenge the ruling on the field:

If you are interested in Mexico, voter security, or both, this old-school Snopes post is well worth a read. It is rare that I recommend Snopes, but credit where credit is due. To be fair, it was 2015. And that was a different time:

As Loyola University Law School professor Justin Levitt (who has been tracking allegations of voter fraud for years) noted in 2014, voter ID requirements generally target only a single, rare form of fraud while leaving the door wide open for other (more problematic) forms:

Election fraud happens. But ID laws are not aimed at the fraud you’ll actually hear about. Most current ID laws aren’t designed to stop fraud with absentee ballots (indeed, laws requiring ID at the polls push more people into the absentee system, where there are plenty of real dangers). Or vote buying. Or coercion. Or fake registration forms. Or voting from the wrong address. Or ballot box stuffing by officials in on the scam.

“Plenty of real dangers.” Once again, it turns out that we have always been at war with Eastasia. Once again—America picks the wrong year to stop sniffing glue.

Election epistemology

Ultimately, the voter is in the same position with the security of the 2020 election as with Chinese biolab security: either we take an opaque and unaccountable institution’s word that nothing untoward could possibly have happened, or we don’t.

We know that this institution can do a very impressive job of investigating itself. We see that in 2015 and 2019, it did not think it was very secure. But in 2020 it decided it was very secure indeed! Perhaps it improved. Stranger things have happened.

Yet when we ask to look into the matter—it gives us the finger. Then pulls out its club. What other message should we receive? Why else would we go straight to ad baculum, with barely even a cursory stop at ad verecundiam?

The argument from authority works if and only if said authority must be inherently trusted on the subject—like the Pope’s decisions on Catholic doctrine. (No serious Catholic ever confused the Pope with a psychic—but this is honestly and sadly what most atheists, maybe even most Protestants, think “papal infallibility” means.)

The Pope is tautologically correct about Catholic doctrine. The math community is not tautologically correct about math—but good luck beating them at it. The same with physics, or geology. The chiropractic and acupuncture communities (I, foolishly and perhaps wrongly, believe) are complete bunk and a menace to the public health. So in which of these categories do our election experts (like Prof. Levitt) belong?

If to know that our elections are not ganked we must take the word of some community, we might as well not have elections at all. We should bend over, think of England, and entrust all our government to this community—this marvelous unwatched watchman—as we apparently trust it implicitly, completely, and unaccountably.

The problem with trusting election security to election experts is just the problem of finding an election expert without a professional or ideological conflict of interest. Moreover, even the false perception of a conflict is almost as bad as a real conflict.

In the real world, the voter is perfectly that aware that “election expert” is no more than a credential conferred by an institution—or rather, a set of institutions. All such institutions appear to share exactly the same ideological conflict of interest; so we can regard them as a single institution. Unconditional trust in a sacred institution may be a perfectly fine system of government. It is hardly a reason to hold elections.

But while Gray Mirror will never be surpassed for nihilism, ours is a positive nihilism. If we did believe in elections (lol), how would we do them right?

The presentee election

Once you stop trusting power just because it is strong, how can that trust be rebuilt? One way is a presentee election.

A presentee election is one in which the government knows who all its citizens are, and each vote is one citizen present before an independent witness on election day. Voters who can’t come to a booth can have a witness come to them. Simple as that!

The presentee election is just counting who is willing to be present on each side. To differentiate itself from a “voter-suppression scheme,” it goes much farther than our current shambles in making sure registration is universal and voting is trivial.

The purpose of the presentee election is to trivially defeat all the exploits that Prof. Levitt (2015 “plenty of real dangers” edition) mentions—and any others anyone can imagine. As Snopes says of Mexico in the ‘90s, “many citizens no longer trusted the electoral process.” And have Americans ever been too proud to learn from Mexico?

Probably the most similar design, though, is that of Israel. There are few cultures in which the principle of “trust, but verify” is more deeply embedded. The sabra mind is comfortable and capable in designing and inhabiting Byzantine systems—ones which assume that everyone will cheat if they can possibly get away with it. We cannot copy Israel’s electoral architecture directly; but we have plenty to learn from it.

The best thing about Israeli elections is their simplicity. The designer understood that the goal of an election is not just to be fair—but to demonstrate that fairness. And the audience of any demo can hardly be blamed for being unimpressed. Communication is the task of the speaker, not the audience.

The palpably secure election

What we need is a palpably secure election—any fool can look at it and see that it is secure, without trusting any institution or any experts.

Because if fools don’t count, why have elections at all? As Wikipedia says of Israel’s elections, “the system is simple to use for those with limited literacy.” Such simple, yet grounded, voters are the deep fonts of wisdom which every democracy needs.

In a world where an electorally significant number of voters do not trust any experts at all, the only practical way to regain their trust is to conduct an election so simple that everyone can see its fairness with their own two eyes. This is the presentee election.

Everyone in media is having a tough March. I wouldn’t want to be CNN right now! Gray Mirror is no exception—we are mostly flat on the month. While this is probably due to my own bad choices—if you’d like to know more, you’ll still have to: